The Boston Jewish Film Festival is a sprawling thing, one that takes place in over a half dozen venues and, I suspect, as many municipalities. There are some of them that public transit folks like me just can't reach - good luck getting to Danvers or West Newton, for instance. Well, I can get to West Newton. Getting home from there is an entirely different matter.

Mary and Max wasn't quite my first choice Thursday night. I figured that The Girl on the Train would be less likely to show up for a regular run and it would be nifty to see Emilie Duquennes in something new, as not much of what she has done since Brotherhood of the Wolf has made it to the Boston area. Too early, though, for me to get back to Cambridge from Waltham.

Mary and Max

* * * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 12 November 2009 at Coolidge Corner Theatre #1 (Boston Jewish Film Festival)

It's interesting how certain things seem to arrive in clusters. Stop-motion animation never seemed to disappear quite so completely as the traditional cel-based form, but what has appeared over the last year or so has been an unexpected bounty. Not just in amount, but that Australia has turned out two of these films ($9.99 and Adam Elliot's Mary and Max) that are both well-produced and perhaps more suited to the boutique house than the multiplex.

Mary Daisy Dinkle (voice of Bethany Whitmore) is an eight-year-old girl living outside of Melbourne, ostracized for the birthmark on her forehead and dealing with weird parents. Curious about where babies come from in America (in Australia, they're found at the bottom of beer glasses), she writes to an address she pulls out of the New York phone book randomly. The recipient happens to be Max Jerry Horovitz (voice of Philip Seymour Hoffman), who is obese, in his mid-forties, and has a hard time relating to the outside world. He writes back, though, starting a correspondence that will continue for years.

By then, Mary will be voiced by Toni Collette, a transition that is handled so smoothly the audience may never realize that different actress's voice the character at different ages. It's a very nice cast - Whitmore and Collette are perfect fits for Mary as she goes through her ups and downs, while Hoffman takes on a tone that is gruff and maybe a little combative. He does a nice job in making it clear how Max, by nature of his mental condition, has to really concentrate on how to interact with others. Eric Bana is good as Mary's next-door neighbor, Damien, and Barry Humphries does a fine job as the film's narrator, adding a great deal of dry wit to what could feel like dull or needless exposition.

Which is good, because the film uses him a lot. At times, this is a little frustrating; it flies in the face of the "show, don't tell" dictum. What it winds up doing, though, is emphasizing that these two pen pals only know each other through their letters, and lets us experience that friendship the same way, even though we are also seeing them do things they don't write about and are fed information that wouldn't be in the letters. It's not necessarily an easy device to accept, but it works much better than it does in other narration-heavy films. That it allows Elliot to avoid awkward lip-sync issues is a bonus.

A large bonus, though, as it would be a shame if the impressive animation were sabotaged by that (which seems especially tricky in stop-motion). The character animation is remarkably smooth; there's no stuttering, and the characters neither look like hard plastic nor pick up fingerprints or other deformations that often remind the viewer that someone is manipulating models. Some of the models are just excellent: I love the design for Mary, for instance, which is simple and very expressive, and moves from child to adult fantastically well. The same is true for Damien, and I wonder if they wound up being the two best-designed characters because the need to age them recognizably meant keeping them simple. Some of the other characters are a little busy - Max looks like a lighter-skinned Shrek, for instance. I love the model of New York, though.

The story is good, as well. It's a very true depiction of isolated people making tentative connections, none of them perfect. Characters get angry and hurt each other badly, and people die even though they might be all someone else has. It's a tightrope between hilarious and depressing, with some moments able to fit under either category. Thanks to the efforts of Elliot, the animators, and the voice actors, Mary and Max are almost always sympathetic characters, even when we want them to act differently, and well worth following.

According to a subtitle, Mary and Max was inspired by actual events, and despite the often crazy embellishments, I believe that. It's a genuine, touching story of friendship, even when that friendship is hard.

Also at HBS.

Monday, November 30, 2009

Made in Japan: Ichi and United Red Army

I've got real questions about the marketing and distribution of Ichi. This isn't a complaint against the fine folks at Kendall Square who were cool enough at the ticket window that I dropped some cash at the concession stand even though I really wasn't that hungry(*), but there was no advance word of this screening - I stumbled upon it quite accidentally looking at the day's showtimes in Google's movie page. It's being put out on DVD and Blu-ray by FUNImation, supposedly with a theatrical run between now and then, and I assume that the Warner Brothers logo at the front and back meant they have something to do with it, either producing it in Japan or handling American theatrical distribution.

There were maybe half a dozen of us there, despite the theater practically being on the MIT campus. You'd think it would be possible to get more otaku out to see it than this handful. I've got to consider that a bit of a marketing fail.

I also wonder why they're making a bit of a splash with this Haruka Ayase movie from 2008, when as far as I can tell there's no U.S. distribution for the superior Cyborg She.

(*) They probably knew what they were doing, sending me in - the margin on a Pocky & Coke is probably much better than that of a ticket. It makes me wonder if theaters could succeed by drastically cutting prices, even down to nothing, and making up what they lose on individual ticket sales with volume, both in terms of tickets and snacks.

Ichi

* * ½ (out of four)

Seen 5 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #3 (preview)

It is one of the oldest tricks in the book, despite having rather limited success, as far as I can tell: Take a franchise that has seen better days and revive it, only the new protagonist is no longer a middle-aged man, but a young, attractive girl. Maybe she's an apprentice, a long-lost (grand)daughter, or just someone who stumbled upon the legacy. The point is, the new product has got the unstoppable combination of brand awareness and sex appeal - how can it fail?

And yet, this template has seldom been a roaring success, and it's no different with Ichi, which almost certainly will not see the same sort of success as Zatoichi (26 movies, a TV series, and a Takeshi Kitano remake). Maybe it's the inevitable result of thinking in terms of product and franchise from the start, or that the alchemy of a hit is almost impossible to replicate just by following a recipe. Even franchise reboots that stick close to the source material often fail to catch lightning in a bottle for a second time; taking that further calculated step can just make it more alienating.

So we have Ichi (Haruka Ayase), a blind goze singer wandering on her own. Despite wearing rags and often sleeping outside, though, she's not completely helpless; far from it, she carries a short sword and her backslashing accuracy with it is lethal. She arrives in the town of Bito with ronin Toma Fujihara (Takao Osawa), allowing the local yakuza to assume that he is the one who killed a handful of bandits, even though he freezes when the time comes to draw his sword. Local yakuza leader Toraji Shirakawa (Yosuke Kubozuka) hires Toma to help them fight the Banki-to gang, named for its monstrous leader, Banki (Shido Nakamura). Ichi's curiosity is piqued when she finds out that Banki once knew a certain blind swordsman.

The samurai film and the western are closely related genres, and Ichi could certainly pass for an oater if it swapped its samurai swords for six-shooters. You've got a gang choking the life out of a town, local authorities (which is what the yakuza effectively were, at this point in time) unable to stop them, and a new sheriff in town who relies heavily on a trusted deputy. When the yakuza and bandits line up at opposite ends of a deserted street, a little Morricone on the soundtrack would sound just about right.

Unfortunately, while the ambiance of those scenes is just right and the action scenes which play out startlingly quickly even in slow motion can be exciting, the rest of the movie frequently doesn't measure up. The story isn't bad, even if it is pretty standard fare. Director Fumihiko Sori never seems to commit to a tone for the movie, though. The movie swings from melodrama to earnest sadness, and while the audience can see the skeleton of a love story, there's not a lot of passion to make it a great one.

The main problem, though, is that the cast is for the most part too young and good-looking. Even after we've seen the rape which saw Ichi banished from her troupe, Haruka Ayase is just too beautiful, with a face too perfectly unlined. It's not wholly her fault, of course - she plays the scenes where she is being put through the wringer well enough; it's just where we're supposed to look at her and know things have happened to her that she falls short. And someone else decided that her rags should look "distressed" rather than "tattered", or that she should always be clean and perfectly made-up and coiffed. The end result, though, is that we look at her and see her beauty rather than her character - she just doesn't give Ichi the proper gravity. Osawa is much the same, only he does a thing where he winces and looks tortured every time he starts to draw his sword. The two banter well enough together, and I might like them in a romantic comedy, but in a samurai movie (or a western), they look like kids in their high school play - dressed up in the costumes, solemnly playing their roles, but just unable to give the characters enough weight.

They can handle action, and when that's going on, the movie works well enough to be entertaining. It wants to be something a bit heftier, though, and neither Sori nor his cast has the gravitas to completely pull it off.

Also at HBS

Jitsuroku rengô sekigun: Asama sansô e no michi (United Red Army)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 9 November 2009 at the Harvard Film Archive (special engagement)

There are two ways to look at Koji Wakamatsu's three-hour film United Red Army. The glass-half-full version is that it is a fantastically complete and detailed history of the titular group that gives special attention to some of that history's most (in)famous chapters. The other perspective is that it is a harrowing true tale of horror surrounded by exposition and epilogue that serves to distract from the really good parts. It's not a bad sign that even the glass-half-empty version admits that the film has a very solid core.

Wakamatsu's film separates into three acts even easier than most. The first tells us in documentary style how various protest movements in 1960s Japan formed and later radicalized, leading to two of the most radical, the Red Army Faction and Revolutionary Left Faction, to become the Unified (later United) Red Army. The second has the URA holed up in the Japanese Alps, hiding from police as the leaders grow more and more autocratic, visiting violent punishment on their followers. In the aftermath, five members hole up in the Asama Mountain Lodge ski resort, taking the manager's wife hostage while the police laid siege for a month.

Wakamatsu's ambition with United Red Army is impressive and admirable, but also quite frankly daunting for those without prior knowledge of the subject. The film has literally dozens of characters, many of whom seem to be included for completeness's sake. People will be introduced and built up as if they were major characters only to be arrested and disappear twenty minutes later (don't get too attached to Tak Sakaguchi, likely the most familiar member of the cast for western audiences). The opening act covers roughly twelve years and features an odd combination of narration, stock footage, and scenes that seem more like crime-show recreations (in black-and-white to match the stock footage) in tone than part of a dramatic feature. The end gives us information on what happened to the group's members over the ensuing thirty years, enough information that the subtitles may change faster than the audience can read them. It is without a doubt informative, and Wakamatsu does an admirable job of not making these purely informational segments dry, but it is occasionally overwhelming.

What is somewhat dry, oddly, is the film's third act, as five escaped URA men barricade themselves in a cottage with a hostage. This is a genre film staple, but stuck on the tail end of this movie, it has a lot of issues: It brings some very minor characters to the forefront, and it never gives us a glance of the other side of the siege. In some ways, that's consistent with the rest of the movie - though there is some exposition to set the stage in the first act, Wakamatsu tells the story almost entirely from within the URA - but it reduces tension, especially since hostage Yasuko Muta (Karou Okunuki) is barely a factor. It's also hard to return to seeing them somewhat sympathetically after what had come before.

And what comes before, the middle of the movie, is dynamite. Wakamatsu is known in part for his sympathies with radical politics, but he doesn't flinch from how the months in the Japanese Alps are a microcosm on how communism went horribly wrong around the world: A movement dedicated to liberating workers from the ruling class develops its own despots, and failing to adhere to slogans and dogma is considered treasonous. Go Jibiki and Akie Namiki portray Tsuneo Mori and Hiroko Nagata as a terrifyingly complementary of true believers, Mori loud and bullying and Nagata icily terrifying - when Nagata comments that a pregnant member of the group is a threat because she thinks of her child as belonging to her rather than the party, the horrifying sincerity comes through even via subtitles. They stand in stark contrast to their victims, especially Maki Sakai's Mieko Toyama. Toyama is one of the characters we've seen since early on in the film, and though the film doesn't present her as an innocent, Sakai makes her sympathetic; we get the feeling that she followed her best friend into the movement, and winds up suffering because she is not at heart a violent person.

This central section has its problems as a movie, at least from a certain perspective. Many screenwriters would probably streamline the movement between bases and composite some characters, as at one point the same basic story (one woman and two men are tortured for not being able to "self-criticize" properly) is playing out in two locations. Even with that, it's devastatingly effective, as Wakamatsu escalates the violence and madness at a perfect clip, making it even worse by interspersing scenes showing that certain characters going to be are in trouble for just not being hardcore enough. The violence is brutal and comes across that way - it would be easy for this section to become a horror movie where the various deaths give us a secret thrill, or for the filmmaker's sympathy to the general cause to inject a hint of justification, but that doesn't happen - what we see is horrible in every way.

It's so good that at times I wished it were the whole movie, with a little narrative streamlining and just enough of what precedes and follows it included to give context. But, as the film reminds us, history is messy, and doesn't fit the standard form of a narrative feature.

Also at HBS

There were maybe half a dozen of us there, despite the theater practically being on the MIT campus. You'd think it would be possible to get more otaku out to see it than this handful. I've got to consider that a bit of a marketing fail.

I also wonder why they're making a bit of a splash with this Haruka Ayase movie from 2008, when as far as I can tell there's no U.S. distribution for the superior Cyborg She.

(*) They probably knew what they were doing, sending me in - the margin on a Pocky & Coke is probably much better than that of a ticket. It makes me wonder if theaters could succeed by drastically cutting prices, even down to nothing, and making up what they lose on individual ticket sales with volume, both in terms of tickets and snacks.

Ichi

* * ½ (out of four)

Seen 5 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #3 (preview)

It is one of the oldest tricks in the book, despite having rather limited success, as far as I can tell: Take a franchise that has seen better days and revive it, only the new protagonist is no longer a middle-aged man, but a young, attractive girl. Maybe she's an apprentice, a long-lost (grand)daughter, or just someone who stumbled upon the legacy. The point is, the new product has got the unstoppable combination of brand awareness and sex appeal - how can it fail?

And yet, this template has seldom been a roaring success, and it's no different with Ichi, which almost certainly will not see the same sort of success as Zatoichi (26 movies, a TV series, and a Takeshi Kitano remake). Maybe it's the inevitable result of thinking in terms of product and franchise from the start, or that the alchemy of a hit is almost impossible to replicate just by following a recipe. Even franchise reboots that stick close to the source material often fail to catch lightning in a bottle for a second time; taking that further calculated step can just make it more alienating.

So we have Ichi (Haruka Ayase), a blind goze singer wandering on her own. Despite wearing rags and often sleeping outside, though, she's not completely helpless; far from it, she carries a short sword and her backslashing accuracy with it is lethal. She arrives in the town of Bito with ronin Toma Fujihara (Takao Osawa), allowing the local yakuza to assume that he is the one who killed a handful of bandits, even though he freezes when the time comes to draw his sword. Local yakuza leader Toraji Shirakawa (Yosuke Kubozuka) hires Toma to help them fight the Banki-to gang, named for its monstrous leader, Banki (Shido Nakamura). Ichi's curiosity is piqued when she finds out that Banki once knew a certain blind swordsman.

The samurai film and the western are closely related genres, and Ichi could certainly pass for an oater if it swapped its samurai swords for six-shooters. You've got a gang choking the life out of a town, local authorities (which is what the yakuza effectively were, at this point in time) unable to stop them, and a new sheriff in town who relies heavily on a trusted deputy. When the yakuza and bandits line up at opposite ends of a deserted street, a little Morricone on the soundtrack would sound just about right.

Unfortunately, while the ambiance of those scenes is just right and the action scenes which play out startlingly quickly even in slow motion can be exciting, the rest of the movie frequently doesn't measure up. The story isn't bad, even if it is pretty standard fare. Director Fumihiko Sori never seems to commit to a tone for the movie, though. The movie swings from melodrama to earnest sadness, and while the audience can see the skeleton of a love story, there's not a lot of passion to make it a great one.

The main problem, though, is that the cast is for the most part too young and good-looking. Even after we've seen the rape which saw Ichi banished from her troupe, Haruka Ayase is just too beautiful, with a face too perfectly unlined. It's not wholly her fault, of course - she plays the scenes where she is being put through the wringer well enough; it's just where we're supposed to look at her and know things have happened to her that she falls short. And someone else decided that her rags should look "distressed" rather than "tattered", or that she should always be clean and perfectly made-up and coiffed. The end result, though, is that we look at her and see her beauty rather than her character - she just doesn't give Ichi the proper gravity. Osawa is much the same, only he does a thing where he winces and looks tortured every time he starts to draw his sword. The two banter well enough together, and I might like them in a romantic comedy, but in a samurai movie (or a western), they look like kids in their high school play - dressed up in the costumes, solemnly playing their roles, but just unable to give the characters enough weight.

They can handle action, and when that's going on, the movie works well enough to be entertaining. It wants to be something a bit heftier, though, and neither Sori nor his cast has the gravitas to completely pull it off.

Also at HBS

Jitsuroku rengô sekigun: Asama sansô e no michi (United Red Army)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 9 November 2009 at the Harvard Film Archive (special engagement)

There are two ways to look at Koji Wakamatsu's three-hour film United Red Army. The glass-half-full version is that it is a fantastically complete and detailed history of the titular group that gives special attention to some of that history's most (in)famous chapters. The other perspective is that it is a harrowing true tale of horror surrounded by exposition and epilogue that serves to distract from the really good parts. It's not a bad sign that even the glass-half-empty version admits that the film has a very solid core.

Wakamatsu's film separates into three acts even easier than most. The first tells us in documentary style how various protest movements in 1960s Japan formed and later radicalized, leading to two of the most radical, the Red Army Faction and Revolutionary Left Faction, to become the Unified (later United) Red Army. The second has the URA holed up in the Japanese Alps, hiding from police as the leaders grow more and more autocratic, visiting violent punishment on their followers. In the aftermath, five members hole up in the Asama Mountain Lodge ski resort, taking the manager's wife hostage while the police laid siege for a month.

Wakamatsu's ambition with United Red Army is impressive and admirable, but also quite frankly daunting for those without prior knowledge of the subject. The film has literally dozens of characters, many of whom seem to be included for completeness's sake. People will be introduced and built up as if they were major characters only to be arrested and disappear twenty minutes later (don't get too attached to Tak Sakaguchi, likely the most familiar member of the cast for western audiences). The opening act covers roughly twelve years and features an odd combination of narration, stock footage, and scenes that seem more like crime-show recreations (in black-and-white to match the stock footage) in tone than part of a dramatic feature. The end gives us information on what happened to the group's members over the ensuing thirty years, enough information that the subtitles may change faster than the audience can read them. It is without a doubt informative, and Wakamatsu does an admirable job of not making these purely informational segments dry, but it is occasionally overwhelming.

What is somewhat dry, oddly, is the film's third act, as five escaped URA men barricade themselves in a cottage with a hostage. This is a genre film staple, but stuck on the tail end of this movie, it has a lot of issues: It brings some very minor characters to the forefront, and it never gives us a glance of the other side of the siege. In some ways, that's consistent with the rest of the movie - though there is some exposition to set the stage in the first act, Wakamatsu tells the story almost entirely from within the URA - but it reduces tension, especially since hostage Yasuko Muta (Karou Okunuki) is barely a factor. It's also hard to return to seeing them somewhat sympathetically after what had come before.

And what comes before, the middle of the movie, is dynamite. Wakamatsu is known in part for his sympathies with radical politics, but he doesn't flinch from how the months in the Japanese Alps are a microcosm on how communism went horribly wrong around the world: A movement dedicated to liberating workers from the ruling class develops its own despots, and failing to adhere to slogans and dogma is considered treasonous. Go Jibiki and Akie Namiki portray Tsuneo Mori and Hiroko Nagata as a terrifyingly complementary of true believers, Mori loud and bullying and Nagata icily terrifying - when Nagata comments that a pregnant member of the group is a threat because she thinks of her child as belonging to her rather than the party, the horrifying sincerity comes through even via subtitles. They stand in stark contrast to their victims, especially Maki Sakai's Mieko Toyama. Toyama is one of the characters we've seen since early on in the film, and though the film doesn't present her as an innocent, Sakai makes her sympathetic; we get the feeling that she followed her best friend into the movement, and winds up suffering because she is not at heart a violent person.

This central section has its problems as a movie, at least from a certain perspective. Many screenwriters would probably streamline the movement between bases and composite some characters, as at one point the same basic story (one woman and two men are tortured for not being able to "self-criticize" properly) is playing out in two locations. Even with that, it's devastatingly effective, as Wakamatsu escalates the violence and madness at a perfect clip, making it even worse by interspersing scenes showing that certain characters going to be are in trouble for just not being hardcore enough. The violence is brutal and comes across that way - it would be easy for this section to become a horror movie where the various deaths give us a secret thrill, or for the filmmaker's sympathy to the general cause to inject a hint of justification, but that doesn't happen - what we see is horrible in every way.

It's so good that at times I wished it were the whole movie, with a little narrative streamlining and just enough of what precedes and follows it included to give context. But, as the film reminds us, history is messy, and doesn't fit the standard form of a narrative feature.

Also at HBS

Thursday, November 05, 2009

35 Shots [of Rum] & The Canyon

When I saw these two movies lined up as my Monday and Tuesday - 35 Shots of Rum was the Chlotrudis movie of the week, The Canyon a likely single-week run that would only fit in Tuesday because of my desire to watch the last game(s) of the World Series - I was figuring that I would like The Canyon more, on the basis that while horror/thriller/suspense films could maybe use a little more character work, it wouldn't kill Claire Denis to have her characters do something exciting.

I still believe this in general, even if I wound up liking 35 Shots of Rum a whole lot more than The Canyon. 35 Shots is an interesting movie to watch, and a poster boy for the idea of "viewing films actively", but I did fidget a lot while watching it (the couple yakking behind me didn't help - just because it's in French and I'm reading subtitles doesn't mean I want to hear you!). It's just that in this case, I wandered into a pretty good Movie Where Nothing Happens (TM) and a fairly dull adventure film.

35 Rhums (35 Shots [of Rum])

* * * (out of four)

Seen 2 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #2 (first-run)

I had an odd experience reading the description in the theater's program for 35 Shots (that's the subtitle that appeared on the print; the poster adds "of Rum", probably a better translation of French title "35 rhums") after viewing the movie. I wouldn't so much say it was inaccurate, even though it didn't really match what I saw. Claire Denis expects the audience to fill in many blanks.

So, let us start with the bare facts. Lionel (Alex Descas) drives a train in the Paris Metro; his friend and co-worker, René (Julieth Mars Toussaint) is retiring. Lionel lives in an apartment with his daughter Joséphine (Mati Diop). Also living in the same building are Noé (Grégoire Colin) - Lionel and Joséphine look in on his cat during his frequent overseas trips - and Gabrielle (Nicole Dogué), a taxicab driver who is friends with all of them. Jo has recently caught the eye of Ruben (Jean-Christophe Folly), a fellow student at her University.

All, other than Noé, are black, although that does not appear to be significant. Or is it? Here, we must start to piece together interpretations, based on what we see of the characters, as Denis is very seldom going to have the characters simply come out and state how they feel about each other, or fully articulate their history. They say enough to indicate that there is plenty of history in some instances, and most audience members will extrapolate a roughly similar chain of events. You have to pay attention, is all.

Which can, admittedly, be tricky. Denis and co-writer Jean-Pol Fargeau do not overburden the film with a great deal of plot or dialogue. This is the sort of film that spends a great deal of time on following its characters as they go about everyday tasks: Lionel quietly drives his train, or he and Joséphine prepare dinner. Noé talks in vague terms about a new job. The two scenes that serve as the film's turning point are extremely low key - a scene in a bar is full of people pointedly not talking to each other, while the next finishes with a reaction to something that has happened off-screen. As someone who tends to like more active movies, I fully sympathize with anybody who loses patience here.

Fortunately, star Alex Descas is excellent at not saying anything. There is something occasionally rather cold about his Lionel; especially in his dealings with Gabrielle, he can seem quietly cruel. But there's also a warmth in his scenes with Mati Diop that rings very true - not demonstrative all the time, and they can get angry at each other, but something about his rugged, worn face lightens.

Diop is a good complement for him in that regard; though she mirrors some of Lionel's somewhat defensive attitude, Joséphine seems a bit more comfortable with the world around her, and also slips into the position of being daddy's girl without being immature or selfish. It's easy to imagine a background in which Lionel is an immigrant who will never be as at-home in Paris as his daughter. Dogué and Colin, as well as Toussaint and Folly, play characters that we know mainly through their relationships to Lionel and Joséphine, but make them much more complete than plot devices.

Denis and company bring them together in interesting ways. With the dialogue relatively low, the environments play an important part. Compare the tidy apartment Lionel and Joséphine share to that of Noé, for example. Examine the plentiful shots of railroad tracks; on the one hand, they indicate constraints, but the complexity of the network suggests the opposite. Note how Agnès Godard's camera lingers over a location late in the film, how different it is from where we've spent most of our time.

What does all this mean? That's up to the audience, to a certain extent - this is the sort of film where how much you take from it is tied to what you bring and how much effort you make. I've got my ideas, and they appear to be different from those of the person who wrote the program. But that's okay; it makes the film an enjoyable one to talk about.

Also at HBS

The Canyon

* * (out of four)

Seen 3 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #7 (first-run, digital projection)

I skipped The Canyon at a festival this summer; it was only playing once and I figured its cast and story gave it a better chance of hitting American theaters and video than the sort-of-French, sort-of-sci-fi film also only playing once across the street. So, three and a half months later, the choice is vindicated - it did play Boston a couple weeks ahead of its video release... and the other movie was better.

The frame on The Canyon isn't bad; A pair of good-looking young people from Chicago have just eloped in Vegas, and have come to Arizona for their honeymoon. Nick (Eion Bailey) is eager to spend the weekend taking a mule down the Grand Canyon, but that's not something that can be done on the spur of the moment; you need a permit months in advance. They meet Henry (Will Patton), a guide who claims to know the right hands to grease, and while Lori (Yvonne Strahovski) is skeptical, she goes along with it. Of course, things don't go wrong until they're halfway down.

The best part of The Canyon is in the title; though I doubt that the park service allowed director Richard Harrah to shoot the bulk of the action there (and the credits point to a Utah shoot), the outdoor photography is frequently beautiful; it's a shame that Harrah and cinematographer Nelson Cragg didn't make a little more use of it. There are some nice backgrounds, but Harrah doesn't give us that great a sense of the geography. When the characters are lost, there's no indication of how far off course they are, and when one has to double back, it doesn't set of specific alarm bells (that's three hours each way, they had to pass X peril, there were a lot of paths that look alike).

That's the big problem with Steve Allrich's script: Nothing is very specific. Nick and Lori are nice enough, but they are awfully generic characters. Henry has a very familiar set of quirks. The conversations the three have seldom contain any memorable lines, and the fight for survival doesn't reflect or parallel what is between Nick and Lori on a personal level much at all. In some ways, I'd be more willing to forgive it when the script or characters have an attack of the stupids (such as deciding to test cell phone reception when hanging off the side of a cliff, rather than after having safely reached the top) if it at least seemed to be something individual, but The Canyon is far too vanilla for that.

The cast does what they can with what little they've got to work with, but they can't spin it into gold. Yvonne Strahovski generally hits the right notes whether asked to be skeptical or capable in an action scene, and doesn't quite seem like she's flipped a switch because the script requires her to be Superwoman now. Eion Bailey isn't quite on the same level; he doesn't quite give Nick enough charm to make his occasional recklessness seem appealing. Will Patton doesn't have to break a sweat to hit the target with Henry; we get the point quick enough and he doesn't bother us because Patton is an old pro, but this is pretty much a paycheck role for him. The whole cast, really.

All that might have been forgiven if there were a moment where the movie really kicks into a higher gear and became an exciting thriller, but it never manages that. It's filled with familiar lost-in-the-wilderness situations, and doesn't vary them a whole lot. With the tension between characters not exactly being played up, the movie needs some more visceral thrills, but instead, it tends to just give the audience more wolves, although in somewhat greater numbers and a little closer each time. Harrah and company handle the technical aspects well - good make-up, action staging, and animal training - but never gets us to the edge of our seats.

You can do great things with this sort of set-up - in theory, The Canyon isn't far off from The Descent or Wilderness in concept, just in details and execution. It just never grabs the audience like those movies do, and doesn't offer us great characterization to fill that void.

Also at HBS

I still believe this in general, even if I wound up liking 35 Shots of Rum a whole lot more than The Canyon. 35 Shots is an interesting movie to watch, and a poster boy for the idea of "viewing films actively", but I did fidget a lot while watching it (the couple yakking behind me didn't help - just because it's in French and I'm reading subtitles doesn't mean I want to hear you!). It's just that in this case, I wandered into a pretty good Movie Where Nothing Happens (TM) and a fairly dull adventure film.

35 Rhums (35 Shots [of Rum])

* * * (out of four)

Seen 2 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #2 (first-run)

I had an odd experience reading the description in the theater's program for 35 Shots (that's the subtitle that appeared on the print; the poster adds "of Rum", probably a better translation of French title "35 rhums") after viewing the movie. I wouldn't so much say it was inaccurate, even though it didn't really match what I saw. Claire Denis expects the audience to fill in many blanks.

So, let us start with the bare facts. Lionel (Alex Descas) drives a train in the Paris Metro; his friend and co-worker, René (Julieth Mars Toussaint) is retiring. Lionel lives in an apartment with his daughter Joséphine (Mati Diop). Also living in the same building are Noé (Grégoire Colin) - Lionel and Joséphine look in on his cat during his frequent overseas trips - and Gabrielle (Nicole Dogué), a taxicab driver who is friends with all of them. Jo has recently caught the eye of Ruben (Jean-Christophe Folly), a fellow student at her University.

All, other than Noé, are black, although that does not appear to be significant. Or is it? Here, we must start to piece together interpretations, based on what we see of the characters, as Denis is very seldom going to have the characters simply come out and state how they feel about each other, or fully articulate their history. They say enough to indicate that there is plenty of history in some instances, and most audience members will extrapolate a roughly similar chain of events. You have to pay attention, is all.

Which can, admittedly, be tricky. Denis and co-writer Jean-Pol Fargeau do not overburden the film with a great deal of plot or dialogue. This is the sort of film that spends a great deal of time on following its characters as they go about everyday tasks: Lionel quietly drives his train, or he and Joséphine prepare dinner. Noé talks in vague terms about a new job. The two scenes that serve as the film's turning point are extremely low key - a scene in a bar is full of people pointedly not talking to each other, while the next finishes with a reaction to something that has happened off-screen. As someone who tends to like more active movies, I fully sympathize with anybody who loses patience here.

Fortunately, star Alex Descas is excellent at not saying anything. There is something occasionally rather cold about his Lionel; especially in his dealings with Gabrielle, he can seem quietly cruel. But there's also a warmth in his scenes with Mati Diop that rings very true - not demonstrative all the time, and they can get angry at each other, but something about his rugged, worn face lightens.

Diop is a good complement for him in that regard; though she mirrors some of Lionel's somewhat defensive attitude, Joséphine seems a bit more comfortable with the world around her, and also slips into the position of being daddy's girl without being immature or selfish. It's easy to imagine a background in which Lionel is an immigrant who will never be as at-home in Paris as his daughter. Dogué and Colin, as well as Toussaint and Folly, play characters that we know mainly through their relationships to Lionel and Joséphine, but make them much more complete than plot devices.

Denis and company bring them together in interesting ways. With the dialogue relatively low, the environments play an important part. Compare the tidy apartment Lionel and Joséphine share to that of Noé, for example. Examine the plentiful shots of railroad tracks; on the one hand, they indicate constraints, but the complexity of the network suggests the opposite. Note how Agnès Godard's camera lingers over a location late in the film, how different it is from where we've spent most of our time.

What does all this mean? That's up to the audience, to a certain extent - this is the sort of film where how much you take from it is tied to what you bring and how much effort you make. I've got my ideas, and they appear to be different from those of the person who wrote the program. But that's okay; it makes the film an enjoyable one to talk about.

Also at HBS

The Canyon

* * (out of four)

Seen 3 November 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #7 (first-run, digital projection)

I skipped The Canyon at a festival this summer; it was only playing once and I figured its cast and story gave it a better chance of hitting American theaters and video than the sort-of-French, sort-of-sci-fi film also only playing once across the street. So, three and a half months later, the choice is vindicated - it did play Boston a couple weeks ahead of its video release... and the other movie was better.

The frame on The Canyon isn't bad; A pair of good-looking young people from Chicago have just eloped in Vegas, and have come to Arizona for their honeymoon. Nick (Eion Bailey) is eager to spend the weekend taking a mule down the Grand Canyon, but that's not something that can be done on the spur of the moment; you need a permit months in advance. They meet Henry (Will Patton), a guide who claims to know the right hands to grease, and while Lori (Yvonne Strahovski) is skeptical, she goes along with it. Of course, things don't go wrong until they're halfway down.

The best part of The Canyon is in the title; though I doubt that the park service allowed director Richard Harrah to shoot the bulk of the action there (and the credits point to a Utah shoot), the outdoor photography is frequently beautiful; it's a shame that Harrah and cinematographer Nelson Cragg didn't make a little more use of it. There are some nice backgrounds, but Harrah doesn't give us that great a sense of the geography. When the characters are lost, there's no indication of how far off course they are, and when one has to double back, it doesn't set of specific alarm bells (that's three hours each way, they had to pass X peril, there were a lot of paths that look alike).

That's the big problem with Steve Allrich's script: Nothing is very specific. Nick and Lori are nice enough, but they are awfully generic characters. Henry has a very familiar set of quirks. The conversations the three have seldom contain any memorable lines, and the fight for survival doesn't reflect or parallel what is between Nick and Lori on a personal level much at all. In some ways, I'd be more willing to forgive it when the script or characters have an attack of the stupids (such as deciding to test cell phone reception when hanging off the side of a cliff, rather than after having safely reached the top) if it at least seemed to be something individual, but The Canyon is far too vanilla for that.

The cast does what they can with what little they've got to work with, but they can't spin it into gold. Yvonne Strahovski generally hits the right notes whether asked to be skeptical or capable in an action scene, and doesn't quite seem like she's flipped a switch because the script requires her to be Superwoman now. Eion Bailey isn't quite on the same level; he doesn't quite give Nick enough charm to make his occasional recklessness seem appealing. Will Patton doesn't have to break a sweat to hit the target with Henry; we get the point quick enough and he doesn't bother us because Patton is an old pro, but this is pretty much a paycheck role for him. The whole cast, really.

All that might have been forgiven if there were a moment where the movie really kicks into a higher gear and became an exciting thriller, but it never manages that. It's filled with familiar lost-in-the-wilderness situations, and doesn't vary them a whole lot. With the tension between characters not exactly being played up, the movie needs some more visceral thrills, but instead, it tends to just give the audience more wolves, although in somewhat greater numbers and a little closer each time. Harrah and company handle the technical aspects well - good make-up, action staging, and animal training - but never gets us to the edge of our seats.

You can do great things with this sort of set-up - in theory, The Canyon isn't far off from The Descent or Wilderness in concept, just in details and execution. It just never grabs the audience like those movies do, and doesn't offer us great characterization to fill that void.

Also at HBS

Monday, November 02, 2009

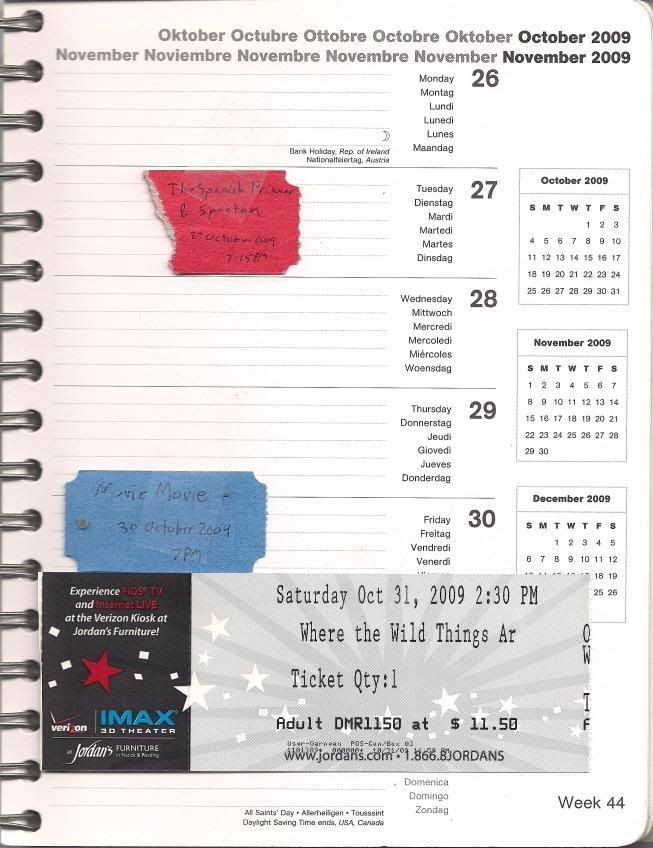

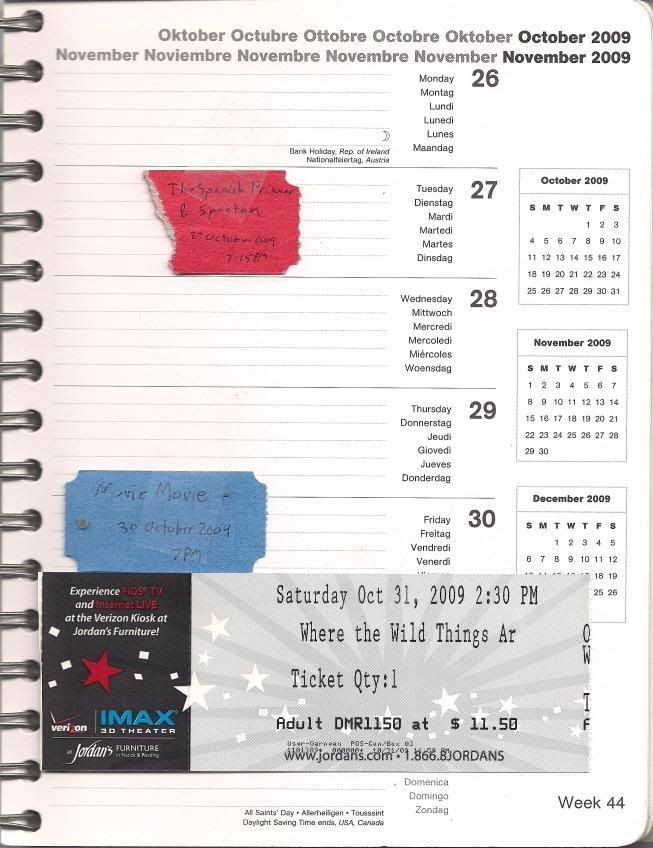

This Week In Tickets: 26 October 2009 to 1 November 2009

If not for the World Series, I'd probably be getting my DVR cleaned up and be making a dent in the metaphorical pile of unwatched screeners/DVDs/BDs hanging around my apartment. Actually, the pile's not metaphorical any more; there's a couple actual piles of things I mean to watch as soon as possible on my coffee table. And it probably wouldn't be a big dent - more of a ding. But I expect to start making it toward the end of the week.

Of course, maybe then there will be more good movies coming out. Right now, I'm really not excited about a whole lot of what's out there, as the relative thin-ness of the last couple weeks shows:

Stubless: American Casino (1 November, 11am, Brattle).

I can't really recommend American Casino when it opens at the Brattle this Wednesday, but it's far from the worst thing coming out this week: Apparently, after threatening to do so for about a year and a half, Magnolia is actually going to put Severed Ways out in a local theater. I saw it at the IFFB last year, and, well, really despised it. I suppose it's inspiring, in a way - if that piece of crap (literally - you get to watch the writer/director/star take a dump in front of you) can get theatrical distribution, there's hope for everyone else with an HD camcorder and a vague idea.

The Spanish Prisoner

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 27 October 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Boston Noir)

I first saw The Spanish Prisoner at the Keystone Theater (which apparently doesn't even seem to have an entry in Cinema Treasures) in Portland, ME, and my older and wiser self has no trouble drawing a parallel between the two: Despite both having what seem to be all the pieces for success, they don't quite work out.

This is one of David Mamet's puzzle movies, and while there's plenty of genuine delight to that, there are also times when the plot seems to require that the movie take place in a parallel universe, where a certain type of clipped speech, odd behavior, and willful obliviousness to what's going on around them make a certain kind of con game more possible. The con certainly seems to have some weak points where it could have completely collapsed.

The cast makes it work very well, though. It is a lot of fun to see Steve Martin play against type as the smooth Jimmy Dell, without irony or much in the way of comedy until his last scene. The stiffness of Campbell Scott works for this character, especially when he's got the too-sweet Rebecca Pidgeon and grumbling Ricky Jay to play off. And I do sort of love how, after playing things very straight and precise from the beginning, Mamet allows things to become whimsical in the last few scenes.

Spartan

* * * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 27 October 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Boston Noir)

I reviewed this back when it originally came out (it's somewhat gratifying to see that while I occasionally cringe at how predictable my structure has become, the actual writing has improved). The second time through, I found I liked it even more. It's a genuinely engrossing thriller, but the second time through, I was more able to appreciate the acting. Val Kilmer just about fell off the map after this (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is the only really noteworthy work he's done since), which is too bad, because this is a nifty performance, a guy who knows how to be a worker bee having to strike out on his own. On the other hand, Kristen Bell would get noticed soon after, being cast in Veronica Mars, and this is an early indication of how great she could be. She may be being wasted in the comedies she's doing now.

I'm kind of surprised this didn't hit the HD formats. I really wish it would.

Movie Movie

* * * (out of four)

Seen 30 October 2009 at the Harvard Film Archive (Debonair: Stanley Donen on Film)

It's a rare, rare thing for this sort of homage/pastiche/parody to work nearly as well as it does. There's a number of reasons for it - Stanley Donen had actually worked in musicals in a career that already spanned 30 years at the time the film was shot, for instance, so he has the comic rhythms down pat, and he doesn't try to modernize them even as he tweaks them.

What's most interesting, perhaps, is the different reaction I had toward both mini-films, even though Donen and writers Larry Gelbart and Sheldon Keller seem to be going for the same deadpan parody in both. The first half, "Dynamite Hands", hit me as a funnier-than-usual idiot movie, pure parody material, while the second half, "Baxter's Beauties of 1933", actually kind of works if you take it seriously. And that's coming from someone who doesn't really like musicals as a rule.

Where the Wild Things Are

* * * (out of four)

Seen 31 October 2009 at Jordan's IMAX Reading (first-run)

When I saw the first stills from Spike Jonze's Where the Wild Things Are, what, two years ago, my first reaction was that that was exactly what a filmed version of Where the Wild Things Are should look like. My second was that that there was no way that book could be made into a feature length movie. It's ten sentences long. To my surprise, the first thought was less true than I expected, the latter maybe a little more so.

I remember the Maurice Sendak book as brighter; even when it was night, everything was sharp. There seems to be a lot more gray and brown in the movie, with Jonze, co-writer Dave Eggers, and company creating a world that seems much more lived-in than the pure fantasy of the book. But that is, perhaps, as it should be - one of the great things about adapting a short work is that you can build it up, elaborate on ideas that interest you without it being at the expense of some other part of the story. It's more creative, and more satisfying, to do that than to cut down and change.

It also makes the result unarguably a Jonze film, and I like that. The way he and cinematographer Lance Acord shoot the opening scenes has me intrigued from the start; it's clearly the work of someone looking to make something more than disposable entertainment for kids, but it's also neither edgy nor overtly nostalgic. He's not talking down to the young folks in the audience, either - there's no obvious sting on the soundtrack when Max finds an ominous set of bones on the Wild Things' island, for instance. The flip side is that the movie does go on a bit too long, dragging at some points in the middle, and the soundtrack is a little too indie at times; for a movie in large part about rage, the music is sometimes too happy.

American Casino

* * (out of four)

Seen 1 November 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Sunday Eye-Opener)

American Casino frustrates the heck out of me. The title mostly refers to to the first half of the movie, which purports to explain how the current financial crisis is the result of parts of the economy being treated as a game of chance, and it's almost completely unwatchable. If the idea is to show how it's all so confusing that even career economists can't understand it, mission accomplished, I guess, but, you know, it's no big accomplishment to demonstrate that something people already don't understand is confusing. It doesn't feel like a successful operation, though, more like sloppy filmmaking.

The second half, where the film zooms in on how it affects people on the ground, especially among Baltimore's African-American community, is much more successful, in large part because it manages a nifty trick: It introduces people to us with the implication that they are maybe not experts, but community support, and once the audience accepts that they are intelligent, capable people, reveals that they are in danger of losing their houses because they are victims. It's as manipulative a technique as any filmmaker uses, but surprising and effective. And if you can't muster up sympathy for your fellow human being, there's an intriguing bit on the environmental toll that this is taking.

So, filmmakers Andrew and Leslie Cockburn manage to do a few things right. Maybe things would have worked out better if they had narrowed their focus, because for all that individual segments are done well, the transitions between them are frequently poor, and the film as a whole feels confused, like the filmmakers knew what they wanted to talk about, but didn't know what they wanted to say.

Of course, maybe then there will be more good movies coming out. Right now, I'm really not excited about a whole lot of what's out there, as the relative thin-ness of the last couple weeks shows:

Stubless: American Casino (1 November, 11am, Brattle).

I can't really recommend American Casino when it opens at the Brattle this Wednesday, but it's far from the worst thing coming out this week: Apparently, after threatening to do so for about a year and a half, Magnolia is actually going to put Severed Ways out in a local theater. I saw it at the IFFB last year, and, well, really despised it. I suppose it's inspiring, in a way - if that piece of crap (literally - you get to watch the writer/director/star take a dump in front of you) can get theatrical distribution, there's hope for everyone else with an HD camcorder and a vague idea.

The Spanish Prisoner

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 27 October 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Boston Noir)

I first saw The Spanish Prisoner at the Keystone Theater (which apparently doesn't even seem to have an entry in Cinema Treasures) in Portland, ME, and my older and wiser self has no trouble drawing a parallel between the two: Despite both having what seem to be all the pieces for success, they don't quite work out.

This is one of David Mamet's puzzle movies, and while there's plenty of genuine delight to that, there are also times when the plot seems to require that the movie take place in a parallel universe, where a certain type of clipped speech, odd behavior, and willful obliviousness to what's going on around them make a certain kind of con game more possible. The con certainly seems to have some weak points where it could have completely collapsed.

The cast makes it work very well, though. It is a lot of fun to see Steve Martin play against type as the smooth Jimmy Dell, without irony or much in the way of comedy until his last scene. The stiffness of Campbell Scott works for this character, especially when he's got the too-sweet Rebecca Pidgeon and grumbling Ricky Jay to play off. And I do sort of love how, after playing things very straight and precise from the beginning, Mamet allows things to become whimsical in the last few scenes.

Spartan

* * * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 27 October 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Boston Noir)

I reviewed this back when it originally came out (it's somewhat gratifying to see that while I occasionally cringe at how predictable my structure has become, the actual writing has improved). The second time through, I found I liked it even more. It's a genuinely engrossing thriller, but the second time through, I was more able to appreciate the acting. Val Kilmer just about fell off the map after this (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is the only really noteworthy work he's done since), which is too bad, because this is a nifty performance, a guy who knows how to be a worker bee having to strike out on his own. On the other hand, Kristen Bell would get noticed soon after, being cast in Veronica Mars, and this is an early indication of how great she could be. She may be being wasted in the comedies she's doing now.

I'm kind of surprised this didn't hit the HD formats. I really wish it would.

Movie Movie

* * * (out of four)

Seen 30 October 2009 at the Harvard Film Archive (Debonair: Stanley Donen on Film)

It's a rare, rare thing for this sort of homage/pastiche/parody to work nearly as well as it does. There's a number of reasons for it - Stanley Donen had actually worked in musicals in a career that already spanned 30 years at the time the film was shot, for instance, so he has the comic rhythms down pat, and he doesn't try to modernize them even as he tweaks them.

What's most interesting, perhaps, is the different reaction I had toward both mini-films, even though Donen and writers Larry Gelbart and Sheldon Keller seem to be going for the same deadpan parody in both. The first half, "Dynamite Hands", hit me as a funnier-than-usual idiot movie, pure parody material, while the second half, "Baxter's Beauties of 1933", actually kind of works if you take it seriously. And that's coming from someone who doesn't really like musicals as a rule.

Where the Wild Things Are

* * * (out of four)

Seen 31 October 2009 at Jordan's IMAX Reading (first-run)

When I saw the first stills from Spike Jonze's Where the Wild Things Are, what, two years ago, my first reaction was that that was exactly what a filmed version of Where the Wild Things Are should look like. My second was that that there was no way that book could be made into a feature length movie. It's ten sentences long. To my surprise, the first thought was less true than I expected, the latter maybe a little more so.

I remember the Maurice Sendak book as brighter; even when it was night, everything was sharp. There seems to be a lot more gray and brown in the movie, with Jonze, co-writer Dave Eggers, and company creating a world that seems much more lived-in than the pure fantasy of the book. But that is, perhaps, as it should be - one of the great things about adapting a short work is that you can build it up, elaborate on ideas that interest you without it being at the expense of some other part of the story. It's more creative, and more satisfying, to do that than to cut down and change.

It also makes the result unarguably a Jonze film, and I like that. The way he and cinematographer Lance Acord shoot the opening scenes has me intrigued from the start; it's clearly the work of someone looking to make something more than disposable entertainment for kids, but it's also neither edgy nor overtly nostalgic. He's not talking down to the young folks in the audience, either - there's no obvious sting on the soundtrack when Max finds an ominous set of bones on the Wild Things' island, for instance. The flip side is that the movie does go on a bit too long, dragging at some points in the middle, and the soundtrack is a little too indie at times; for a movie in large part about rage, the music is sometimes too happy.

American Casino

* * (out of four)

Seen 1 November 2009 at the Brattle Theatre (Sunday Eye-Opener)

American Casino frustrates the heck out of me. The title mostly refers to to the first half of the movie, which purports to explain how the current financial crisis is the result of parts of the economy being treated as a game of chance, and it's almost completely unwatchable. If the idea is to show how it's all so confusing that even career economists can't understand it, mission accomplished, I guess, but, you know, it's no big accomplishment to demonstrate that something people already don't understand is confusing. It doesn't feel like a successful operation, though, more like sloppy filmmaking.

The second half, where the film zooms in on how it affects people on the ground, especially among Baltimore's African-American community, is much more successful, in large part because it manages a nifty trick: It introduces people to us with the implication that they are maybe not experts, but community support, and once the audience accepts that they are intelligent, capable people, reveals that they are in danger of losing their houses because they are victims. It's as manipulative a technique as any filmmaker uses, but surprising and effective. And if you can't muster up sympathy for your fellow human being, there's an intriguing bit on the environmental toll that this is taking.

So, filmmakers Andrew and Leslie Cockburn manage to do a few things right. Maybe things would have worked out better if they had narrowed their focus, because for all that individual segments are done well, the transitions between them are frequently poor, and the film as a whole feels confused, like the filmmakers knew what they wanted to talk about, but didn't know what they wanted to say.

Sunday, November 01, 2009

Fantastic Fest Screener: A Town Called Panic

There were going to be two here, but I couldn't get my other screener to play on my TV. Being that these two movies are European, the DVDs may be PAL, and since none of my DVD-playing devices will play PAL discs, that means using the computer, which hooks up to the TV through a less-than-ideal system: Laptop to router to SlingCatcher to TV/receiver. That worked well enough for one, but not the other, where the screen just filled with pink. I suppose I could watch the movie on the laptop, but I don't have my living room tricked out so that can watch movies on that.

Ideal, of course, would be watching it in Austin, at the Alamo Drafthouse during Fantastic Fest. The EFC guys I've talked to all recommend it, and maybe someday I will. I'm only half-joking when I say it's hard to do, because it conflicts with exciting baseball, but I also feel like I'd be kind of disloyal by going. Fantastic Fest started the same fall as the Brattle's Boston Fantastic Film Festival - perhaps even the same week - but it immediately blew up big while BFFF eventually sputtered out. That's just tremendously frustrating to me - Ned & company would book some great movies, and there would not be a whole lot of people there. Plus, I'd feel kind of like I was cheating on Fantasia - sure, they show a lot of the same movies, but also more Hollywood stuff. It wouldn't quite be selling out, but it strikes me as a step down in coolness.

Why yes, that is a bit of sour grapes... "I can't get out of my day job to head ot Austin for a festival full of nifty movies in cool venues, but it's probably lame anyway!" I think I'm using sour grapes properly there.

Panique au Village (A Town Called Panic)

* * * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 23 October 2009 in Jay's Living Room (DVD via laptop & Slingcatcher)

A Town Called Panic hit me just right tonight; it might not have on another day. It is, you see, an extraordinarily silly animated film, and sometimes one just doesn't feel like silliness. Of course, those times may be when one needs it the most.

Just outside the title town, Cowboy (voice of Stéphane Aubier) and Indian (voice of Bruce Ellison) live with Horse (Vincent Patar). It's Horse's birthday, but they've forgotten, so they trick him into going into town on an errand - it doesn't take much convincing, as he's got a major crush on Madame Longrée (voice of Jeanne Balibar), the horse who runs the music school, while they order some bricks to build Horse a barbecue. Fifty bricks accidentally become fifty million, which, through a series of events that I presume are obvious, inevitably leads to problems with sea monsters and scientists.

Given that two of the main characters are horses who live side-by-side with other talking animals and sea monsters, it's little surprise that this film is animated. The style is a delightfully charming throwback, though: After a smoothly animated title sequence, the picture flips to mostly stop-motion, using toys that sometimes look to have been dug out of the creators' parents' attics. These aren't highly-articulated action figures, but minimally posable things that often have their feet grafted to an immobile base. Or, at least, they look that way - given how things tend to fly through the air, there's likely at least some digital wire removal going on, and the characters will often appear in poses that suggest that they're either more flexible than they first appeared or the filmmakers have built other models which share the same limited range of movement.

Full review at EFC.

Ideal, of course, would be watching it in Austin, at the Alamo Drafthouse during Fantastic Fest. The EFC guys I've talked to all recommend it, and maybe someday I will. I'm only half-joking when I say it's hard to do, because it conflicts with exciting baseball, but I also feel like I'd be kind of disloyal by going. Fantastic Fest started the same fall as the Brattle's Boston Fantastic Film Festival - perhaps even the same week - but it immediately blew up big while BFFF eventually sputtered out. That's just tremendously frustrating to me - Ned & company would book some great movies, and there would not be a whole lot of people there. Plus, I'd feel kind of like I was cheating on Fantasia - sure, they show a lot of the same movies, but also more Hollywood stuff. It wouldn't quite be selling out, but it strikes me as a step down in coolness.

Why yes, that is a bit of sour grapes... "I can't get out of my day job to head ot Austin for a festival full of nifty movies in cool venues, but it's probably lame anyway!" I think I'm using sour grapes properly there.

Panique au Village (A Town Called Panic)

* * * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 23 October 2009 in Jay's Living Room (DVD via laptop & Slingcatcher)

A Town Called Panic hit me just right tonight; it might not have on another day. It is, you see, an extraordinarily silly animated film, and sometimes one just doesn't feel like silliness. Of course, those times may be when one needs it the most.

Just outside the title town, Cowboy (voice of Stéphane Aubier) and Indian (voice of Bruce Ellison) live with Horse (Vincent Patar). It's Horse's birthday, but they've forgotten, so they trick him into going into town on an errand - it doesn't take much convincing, as he's got a major crush on Madame Longrée (voice of Jeanne Balibar), the horse who runs the music school, while they order some bricks to build Horse a barbecue. Fifty bricks accidentally become fifty million, which, through a series of events that I presume are obvious, inevitably leads to problems with sea monsters and scientists.

Given that two of the main characters are horses who live side-by-side with other talking animals and sea monsters, it's little surprise that this film is animated. The style is a delightfully charming throwback, though: After a smoothly animated title sequence, the picture flips to mostly stop-motion, using toys that sometimes look to have been dug out of the creators' parents' attics. These aren't highly-articulated action figures, but minimally posable things that often have their feet grafted to an immobile base. Or, at least, they look that way - given how things tend to fly through the air, there's likely at least some digital wire removal going on, and the characters will often appear in poses that suggest that they're either more flexible than they first appeared or the filmmakers have built other models which share the same limited range of movement.

Full review at EFC.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)