I don't generally make a point of seeing festival films again once they hit the regular theaters, but I will probably make an exception this weekend or next for Drag Me to Hell. The digital file projected in Austin was, well, a digital file, and I'd like to see it on film, from a better seat (I was sitting with some of the eFilmCritic and Cinematical folks, and they wanted to be able to get in and out for photography and the like). It was also a work-in-progress presentation, and though it looked pretty good, there were some scenes that were a little rough. One looks a bit better in the ads being shown, although coming as it does very late in the movie, it's got no business being in the ads.

Having set this review for time-release on HBS/EFC, it's a little amusing to see that while I'm talking about Raimi not losing any of his edge, part of the conversation about this movie has been how some want to skip it in the theater and wait for an unrated DVD/Blu-ray since the theatrical version has a PG-13 rating. I'd advise against that, because this is a tremendously fun audience movie; this sort of horror works much better with a crowd than alone in one's living room. PG-13 is also the movie's natural state; it's not looking to gross the audience out as much as creep them out, and it's not working on a slasher paradigm where most of the characters are cannon fodder to be bumped off in ever more disgusting ways.

As a side note to that, I don't know whether Universal is premiering a new logo with this or whether it's just a one-time thing, but the screening at SXSW didn't have the familiar "sun rising over CGI Earth" bit. Instead, it was a newly-rendered version of the old "zooming in on Earth through cosmic dust clouds" logo. That's kind of fitting, since the movie is a bit of a throwback to the sort of horror movie Universal did back in the day, which had jumps and scares but wasn't looking to exclude kids and teens.

Drag Me To Hell

* * * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 15 March 2009 at the Austin Paramount Theater (SXSW Special Screenings)

Can you believe it's been over twenty years since Evil Dead 2? Considering how much of Sam Raimi's reputation and career is built on that movie and its particular style (he was considered an inspired choice for the Spider-Man films because of it), one would think he'd done more like it, but in fact he's ranged pretty far afield. Even Army of Darkness was something rather different, more PG-13-ish Ray Harryhausen tribute than horror. So while seeing him return to this genre is exciting, it's not unreasonable to wonder whether he's still got something like that in him.

Thankfully, he does. Drag Me to Hell is the Evil Dead 2-iest thing he's done since Darkman, if not ED2 itself, and reassuring in how it demonstrates that his time in the world of of big stars and big budgets hasn't changed him, but rather given him access to and mastery of new tools. Part of the reason why this one manages to retain the feel of an old-school Raimi movie is that it sort of is one - the script was first written years ago, and (I believe) pulled out during the 2007 writers' strike - but give Raimi (along with brother and co-writer Ivan) credit for not deciding to tone it down too much now that they're older and wiser.

When we meet Christine (Alison Lohman), the loan officer is up for a promotion to assistant manager of a Los Angeles bank; the branch manager (David Paymer) has it down to her and less senior but more aggressive Stu (Reggie Lee). An old woman (Lorna Raver) comes in seeking an extension on her mortgage payments; Christine hems and haws but ultimately refuses, noting Mrs. Ganush has had two already. The woman is upset, attacking Christine in the bank's parking garage. Boyfriend Clay (Justin Long) is just glad she's okay, but Christine doesn't think it's over, as weird things start happening and a slick-talking fortune teller (Dileep Rao) tells her she's been made the target of a lamia, a demon which will torment her for a few days before pulling her into Hell.

Full review at EFC, along with several others.

Friday, May 29, 2009

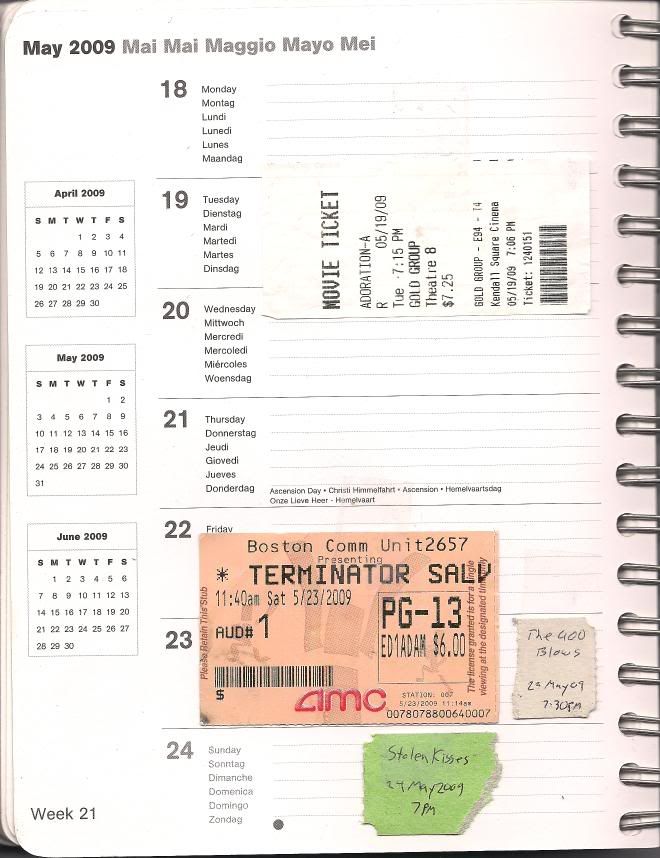

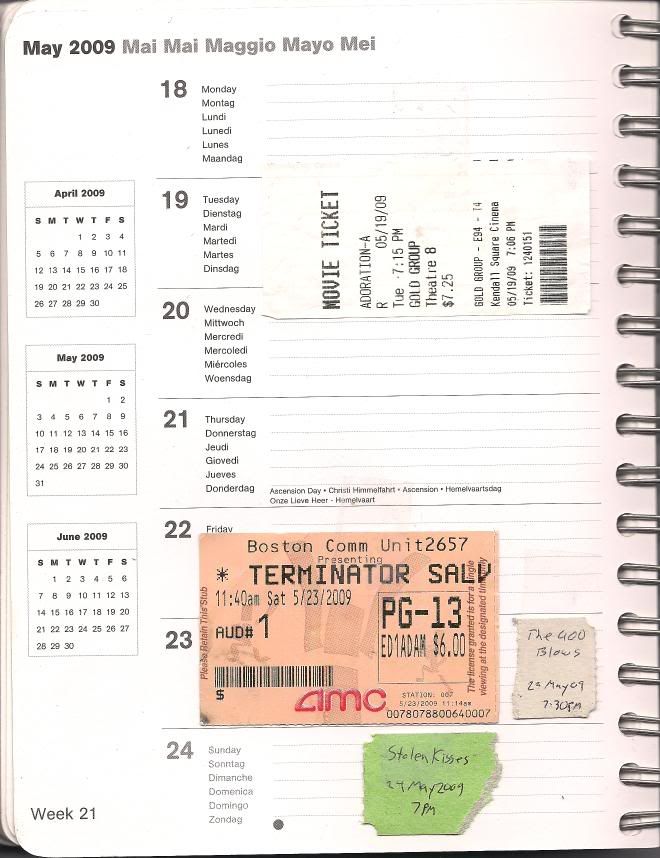

One week at the Kendall: The Merry Gentleman and Adoration

Back when I worked in a movie theater, we almost never had these sort of one-week bookings: Even if a show was a colossal bomb, it would hang around for two weeks minimum, even if the second week was in Theater #3 (at Showcase Cinemas Worcester Downtown (Now the Hanover Theatre), a long narrow closet of a room) for one show a day. It was booked for two weeks, and Sumner Redstone wasn't going to have that print sitting in the booth not earning any money for the second week!

Of course, that was a mainstream theater, while Kendall Square is more of a boutique house, and distributors of independent films are likely happy for any screen they can get, even if it's just for one week - especially if the film is on a calendar, rather than just a random booking the audience knows nothing about. Still, we're lucky enough in the Boston area that the second-run places will pick up independent stuff: The Merry Gentleman only lasted the one week, but Adoration moved over the the Arlington Capitol (though it will already be gone by the time this gets posted). Sugar, after hanging around for a bit at the Kendall, also got its time extended, over at the Somerville Theater.

The Merry Gentleman

* * * (out of four)

Seen 14 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

The Merry Gentleman is one of those movies that appears at the local boutique theater for a blink-and-miss-it one-week engagement with just about zero fanfare, and I probably would have missed it if I hadn't noticed Michael Keaton's name in the credits, both as star and director. He's not the best reason to see the movie - co-star Kelly Macdonald is - but he is the one that got me into a film I might have otherwise skipped.

Keaton plays Frank Logan, a Chicago hitman whose job is making him despondent to the point of being suicidal; he doesn't talk much. Macdonald is Kate Frazier, a nice Scottish girl who, as the film opens, has packed up and left her abusive husband (who is also a policeman, which tends to smooth over any domestic violence reports). One night in December, Kate looks up to see Frank perched on a ledge (she doesn't know someone in her building has just been shot); her shout causes him to fall backward rather than forward. A few days later, they meet again - Frank has a target in her building, and winds up helping her with her Christmas tree. They grow close, but there are secrets and complications: Dave Murcheson (Tom Bastounes), the detective investigating Frank's hits, is also attracted to Kate, and as an audience, we kind of know that they didn't hire Bobby Cannavale to play Kate's husband if he's only going to appear in one wordless scene.

Writer Ron Lazzeretti doesn't fill us in much on how Frank and Kate got to their positions: We never learn why Logan is knocking various people off (or even whether he's a hired gun versus and interested party), nor how Kate wound up in America and married to Michael. We don't need to; our initial introductions to the pair tell us pretty much all we need to about who they are right now, and that's all we need to know. In fact, we probably learn as much about Dave's background as we do about Frank and Kate put together, because Dave is chatty and self-justifying in a way that Frank and Kate are not.

Frank's laconic nature is probably Keaton's biggest stumble as both actor and director, and it's on display early on. It takes what seems like forever for Frank to speak his first lines, including a couple of scenes where he's obviously staying silent to some effect because talking would make much more sense, and all it does is call attention to a gimmick that doesn't have much in the way of payoff. Keaton often seems to be trying very hard to be low-key, and it occasionally looks too studied.

He may just have problems with directing himself, because most of his direction is good, if not necessarily attention-grabbing. He can work various types of tension fairly well, and the rest of the cast seldom falters. He also makes sure to choose some fine collaborators: Lazzeretti's script is peppered with interesting characters, most of whom act in a reasonable way most of the time, and between them Lazzeretti and Keaton avoid spelling more out than necessary. Chris Seager's photography is also very nice; the film has a properly chilly atmosphere, but can still put across the beauty of falling snow, for instance.

That's good, because Macdonald's Kate is the sort who would appreciate it. Macdonald makes it very clear early on that Kate is not defined by her history of domestic violence. She's got that down cold, from Kate always seeming to have her guard up to the earnest but transparent way she tries to explain her black eye, but that's not the entire character. She's a naturally cheerful, good-hearted person, but doesn't overdo it.

The rest of the cast does their jobs well. Bobby Cannavale has a small part but it's an absolutely memorable one (really, you don't want to see anyone with the sort of certainty he does). Darlene Hunt is pleasant in the role of Kate's friend and co-worker. Tom Bastounes has a nifty supporting role as Murcheson, making him likable enough but with just enough hints of maybe being humanly selfish in his dealings with Kate. It's a thoroughly convincing, intriguingly linked group of characters, and the cast does a fine job of bringing them to life.

Looked at as a movie about a sad assassin, the movie is only so-so. The half of the movie that features Kelly Macdonald, though, has a sneaky way of pulling one in, even if it's not what initially caught the eye.

Also at HBS.

Adoration

* * (out of four)

Seen 19 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

Adoration is a movie about unreliable narrators, though it does not necessarily feature one. That sets it up for a bit of trouble, since it isn't quite clever enough to impress with its storytelling gimmick. Using that gimmick takes time away from the actual story, so that falls just a bit short. It's also heavy-handed but kind of vague with the moralizing, so while it has good intentions all around, it's never up to its ambitions.

The narrator is Simon (Devon Bostick), a teenager being raised by his Uncle Tom (Scott Speedman) who, when given an assignment in French class to translate a news story about a Canadian woman whose Middle-Eastern husband placed a bomb in her luggage on her flight to Israel fifteen years ago, does so in the first person; if the bomb had exploded, he concludes, he would never have been born. His teacher Sabine (Arsinée Khanjian) encourages him to explore it further, and the discussion eventually makes its way online, where it spreads from classmates to academics to the general public.

Despite some provocative comments made by Simon's dying grandfather (Kenneth Welsh) which are included in a way as to be misleading, the actual facts become clear fairly rapidly. The film plays it cute for a little while longer, eventually introducing other, even weaker mysteries/ambiguities to unravel. It spends so much time on getting to notice that characters are lying about or omitting events or otherwise emphasizing perspective that when it does present us with a scene that Simon and Tom couldn't possibly know about, it may feel like a cheat, even though writer/director Atom Egoyan has not placed third person omniscient out of bounds.

It's not just the storytelling tricks that Egoyan uses that cause trouble, but the motivation of the characters for using them and the way they go about it. It basically comes down to some characters stirring the pot for the express purpose of stirring the pot, although the profile of agitator doesn't quite fit them. It works well enough in the case of Simon, I suppose - losing his parents the way he did can make a kid dark and the influence of his rather nasty grandfather (both through words and genes) could make up the rest, but I would have liked to be more convinced. It's Sabine that's the real stretch; her deal isn't so far-fetched or unpleasant as to damage the film, but it doesn't provoke the best of reactions. I found myself thinking "really, Atom? that's the way you want to go with this?"

Arsinée Khanjian gets saddled with a lot of stuff like that, frankly, and that Sabine is still being taken somewhat seriously by the audience near the end says good things about her performance. She's helped immensely in this by Scott Speedman, whose character has to actually see the strange stuff up close, acknowledge it, and move past it. He's a good everyman, convincing us of details like how Tom handles a job that sees him despised (tow truck driver). He's nicely unsure of himself, in contrast to Welsh, who is all too confident in his beliefs.

There are other fairly well-done things sprinkled throughout the film. There's some sharp satire of how people respond to these sort of visceral ideas (Maury Chaykin has a sort-of funny cameo here). The flashbacks to a fateful family dinner are fascinating. Bostick plays his role fairly well. As is the case in much of Egoyan's work, what's done well isn't always pleasant, so even when Adoration works, it is more something to be admired than to be enjoyed.

It just doesn't work often enough to rate as a top feel-bad movie. It's got plenty of interesting and/or provocative ideas, but none are given a chance to really get under the audience's skin, and they could be put together much better.

Also at HBS.

Of course, that was a mainstream theater, while Kendall Square is more of a boutique house, and distributors of independent films are likely happy for any screen they can get, even if it's just for one week - especially if the film is on a calendar, rather than just a random booking the audience knows nothing about. Still, we're lucky enough in the Boston area that the second-run places will pick up independent stuff: The Merry Gentleman only lasted the one week, but Adoration moved over the the Arlington Capitol (though it will already be gone by the time this gets posted). Sugar, after hanging around for a bit at the Kendall, also got its time extended, over at the Somerville Theater.

The Merry Gentleman

* * * (out of four)

Seen 14 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

The Merry Gentleman is one of those movies that appears at the local boutique theater for a blink-and-miss-it one-week engagement with just about zero fanfare, and I probably would have missed it if I hadn't noticed Michael Keaton's name in the credits, both as star and director. He's not the best reason to see the movie - co-star Kelly Macdonald is - but he is the one that got me into a film I might have otherwise skipped.

Keaton plays Frank Logan, a Chicago hitman whose job is making him despondent to the point of being suicidal; he doesn't talk much. Macdonald is Kate Frazier, a nice Scottish girl who, as the film opens, has packed up and left her abusive husband (who is also a policeman, which tends to smooth over any domestic violence reports). One night in December, Kate looks up to see Frank perched on a ledge (she doesn't know someone in her building has just been shot); her shout causes him to fall backward rather than forward. A few days later, they meet again - Frank has a target in her building, and winds up helping her with her Christmas tree. They grow close, but there are secrets and complications: Dave Murcheson (Tom Bastounes), the detective investigating Frank's hits, is also attracted to Kate, and as an audience, we kind of know that they didn't hire Bobby Cannavale to play Kate's husband if he's only going to appear in one wordless scene.

Writer Ron Lazzeretti doesn't fill us in much on how Frank and Kate got to their positions: We never learn why Logan is knocking various people off (or even whether he's a hired gun versus and interested party), nor how Kate wound up in America and married to Michael. We don't need to; our initial introductions to the pair tell us pretty much all we need to about who they are right now, and that's all we need to know. In fact, we probably learn as much about Dave's background as we do about Frank and Kate put together, because Dave is chatty and self-justifying in a way that Frank and Kate are not.

Frank's laconic nature is probably Keaton's biggest stumble as both actor and director, and it's on display early on. It takes what seems like forever for Frank to speak his first lines, including a couple of scenes where he's obviously staying silent to some effect because talking would make much more sense, and all it does is call attention to a gimmick that doesn't have much in the way of payoff. Keaton often seems to be trying very hard to be low-key, and it occasionally looks too studied.

He may just have problems with directing himself, because most of his direction is good, if not necessarily attention-grabbing. He can work various types of tension fairly well, and the rest of the cast seldom falters. He also makes sure to choose some fine collaborators: Lazzeretti's script is peppered with interesting characters, most of whom act in a reasonable way most of the time, and between them Lazzeretti and Keaton avoid spelling more out than necessary. Chris Seager's photography is also very nice; the film has a properly chilly atmosphere, but can still put across the beauty of falling snow, for instance.

That's good, because Macdonald's Kate is the sort who would appreciate it. Macdonald makes it very clear early on that Kate is not defined by her history of domestic violence. She's got that down cold, from Kate always seeming to have her guard up to the earnest but transparent way she tries to explain her black eye, but that's not the entire character. She's a naturally cheerful, good-hearted person, but doesn't overdo it.

The rest of the cast does their jobs well. Bobby Cannavale has a small part but it's an absolutely memorable one (really, you don't want to see anyone with the sort of certainty he does). Darlene Hunt is pleasant in the role of Kate's friend and co-worker. Tom Bastounes has a nifty supporting role as Murcheson, making him likable enough but with just enough hints of maybe being humanly selfish in his dealings with Kate. It's a thoroughly convincing, intriguingly linked group of characters, and the cast does a fine job of bringing them to life.

Looked at as a movie about a sad assassin, the movie is only so-so. The half of the movie that features Kelly Macdonald, though, has a sneaky way of pulling one in, even if it's not what initially caught the eye.

Also at HBS.

Adoration

* * (out of four)

Seen 19 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

Adoration is a movie about unreliable narrators, though it does not necessarily feature one. That sets it up for a bit of trouble, since it isn't quite clever enough to impress with its storytelling gimmick. Using that gimmick takes time away from the actual story, so that falls just a bit short. It's also heavy-handed but kind of vague with the moralizing, so while it has good intentions all around, it's never up to its ambitions.

The narrator is Simon (Devon Bostick), a teenager being raised by his Uncle Tom (Scott Speedman) who, when given an assignment in French class to translate a news story about a Canadian woman whose Middle-Eastern husband placed a bomb in her luggage on her flight to Israel fifteen years ago, does so in the first person; if the bomb had exploded, he concludes, he would never have been born. His teacher Sabine (Arsinée Khanjian) encourages him to explore it further, and the discussion eventually makes its way online, where it spreads from classmates to academics to the general public.

Despite some provocative comments made by Simon's dying grandfather (Kenneth Welsh) which are included in a way as to be misleading, the actual facts become clear fairly rapidly. The film plays it cute for a little while longer, eventually introducing other, even weaker mysteries/ambiguities to unravel. It spends so much time on getting to notice that characters are lying about or omitting events or otherwise emphasizing perspective that when it does present us with a scene that Simon and Tom couldn't possibly know about, it may feel like a cheat, even though writer/director Atom Egoyan has not placed third person omniscient out of bounds.

It's not just the storytelling tricks that Egoyan uses that cause trouble, but the motivation of the characters for using them and the way they go about it. It basically comes down to some characters stirring the pot for the express purpose of stirring the pot, although the profile of agitator doesn't quite fit them. It works well enough in the case of Simon, I suppose - losing his parents the way he did can make a kid dark and the influence of his rather nasty grandfather (both through words and genes) could make up the rest, but I would have liked to be more convinced. It's Sabine that's the real stretch; her deal isn't so far-fetched or unpleasant as to damage the film, but it doesn't provoke the best of reactions. I found myself thinking "really, Atom? that's the way you want to go with this?"

Arsinée Khanjian gets saddled with a lot of stuff like that, frankly, and that Sabine is still being taken somewhat seriously by the audience near the end says good things about her performance. She's helped immensely in this by Scott Speedman, whose character has to actually see the strange stuff up close, acknowledge it, and move past it. He's a good everyman, convincing us of details like how Tom handles a job that sees him despised (tow truck driver). He's nicely unsure of himself, in contrast to Welsh, who is all too confident in his beliefs.

There are other fairly well-done things sprinkled throughout the film. There's some sharp satire of how people respond to these sort of visceral ideas (Maury Chaykin has a sort-of funny cameo here). The flashbacks to a fateful family dinner are fascinating. Bostick plays his role fairly well. As is the case in much of Egoyan's work, what's done well isn't always pleasant, so even when Adoration works, it is more something to be admired than to be enjoyed.

It just doesn't work often enough to rate as a top feel-bad movie. It's got plenty of interesting and/or provocative ideas, but none are given a chance to really get under the audience's skin, and they could be put together much better.

Also at HBS.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

This Week In Tickets: 18 May 2009 to 24 May 2009

I'd like to say this got pushed off until Tuesday because I spent the holiday weekend traveling or otherwise doing something out of the ordinary, but I really can't. I mostly spent it right on my own back porch, making a dent in the pile of manga and collected comics I've purchased over the past year. Not a bad way to spend an afternoon or two, although when they started playing baseball, I certainly wished I had some sort of portable radio. It kind of surprises me that I don't; everyone had one or two of those when I was a kid, but nowadays, who needs them when you can carry every song you might want to hear in your pocket, and the vast majority of stations are chain-owned blandness or noxious talk? That includes the sports stations most of the time, but for live sports when you don't want to be chained to the TV, they're pretty useful.

Anyway, I did take a bit of a break from reviewing stuff when I finished the IFFB reviews, using my bus time to finish the first Lensman volume. Triplanetary also included "Masters of Space", and, good gravy... I'd love to see movies or TV made of these stories, because for all E.E. "Doc" Smith could come up with thrilling, cliff-hanging adventure stories, he could not write about people at all. Triplanetary was bearable, in part because it's the 1930s and this is pure pulp and the lurid prose is sincere. It's a total engineer's fantasy, with ideas going form concept to flawless production model in days without management, QA, cost & availability of materials, etc., being an issue. "Masters of Space", though, was written in the sixties, and tries to have soapy elements in it, but everyone is so self-aware that it's maddening. The characters talk about how and why they love each other in this purely rational way that never once rings true, and can we please get back to the ancient astronauts, galaxy-conquering marauders, scientists ascending to near-godhood, and villains intending to use one planet as a bullet to take out another?

Final IFFB update:

22 April 2009 (Wednesday): The Brothers Bloom

23 April 2009 (Thursday): Children of Invention, The Missing Person

24 April 2009 (Friday): Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, In The Loop, Pontypool

25 April 2009 (Saturday): Still Walking, Nollywood Babylon, Lost Son of Havana, Grace

26 April 2009 (Sunday): Herb and Dorothy, Helen, Unmistaken Child, The Escapist

27 April 2009 (Monday): For the Love of Movies, Art & Copy

28 April 2009 (Tuesday): World's Greatest Dad

Finished! Now, to start making reservations and vacation plans for Fantasia. I really need to find some way to get paid to travel the world, going to film festivals and reporting back (c'mon, entertainment websites... just think how much content I could generate for you if I didn't have my day job slowing me down!).

Adoration

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 19 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

I don't think I've seen anything of Atom Egoyan's other than The Sweet Hereafter, and I was young enough then that I missed about half of what was going on. There's some similar themes at play here - survivor's guilt, unhappy families, etc. - but it's never as quietly devastating, and some of the storytelling tools seem... unfair, I guess?

Of course, it's not as if a movie is obligated to play fair, and just because certain things are conventions doesn't mean a specific work has to follow them. So, just because Adoration establishes early on that bits have an unreliable narrator doesn't mean the film can't later on show us an unwitnessed event definitively, especially given how the "unreliable" scenes are shown as being completely untrue. Similarly, a piece of information revealed toward the end seems kind of out of left field, and I found myself sitting there thinking "really? you want to go with that?" It's not a terribly ridiculous coincidence, in retrospect, but when you consider that one of the main themes of this movie is how easy it is to manipulate people with false or incomplete information, it's perhaps not unreasonable to wish the filmmakers did it more artfully.

Also, Egoyan perhaps should have chosen his ending scenes a little more carefully. I didn't come out of the film thinking about media manipulation or prejudice, but about how that kid really did not appreciate the value of nice things. That's a fine violin and phone gone to waste.

Terminator Salvation

* * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

For years, I've been hearing from various sci-fi/film fans about how cool it would be to do a Terminator film that focused on the future war, and I didn't get it. Even when I was younger, I knew a bit about the whole "less is more" thing, and that by giving us small glimpses, James Cameron made it worse than we could imagine. And that was before anybody even considered the idea that there might be a PG-13 Terminator sequel, with the future war a bloodless affair conducted in bright sunlight.

That's part of the problem with Terminator Salvation, a competently made sci-fi action movie with some nice effects and a ridiculously overqualified cast. It leeches the horror out of the idea. In my mind, Skynet never took prisoners - why would they need more than a handful? - and the resistance was always scattered guerrillas, not folks with bunkers and helicopters and the like. They probably weren't as dumb as the characters in this movie could be, but let's be honest - they're really just average sci-fi movie dumb, not recognizing an obvious trap and communicating over frequencies that their enemy could easily eavesdrop on.

The bigger problem is that this movie is conceptually smaller than all the others. All three previous movies hit the audience with the idea that the end was the beginning: It's literally the case for the first and (under-rated) third; they used the time-travel storyline to make the movies closed loops, so that the denouement also happens to be the backstory. The second inverts the idea to suggest that the future was now unpredictable, a wide-open road on which the characters are just now starting their journey. This one is just a disposable side-story, something that happened to John Connor during the part of the story that James Cameron deemed relatively unimportant in The Terminator. It's the stuff of comic book tie-ins, not a story worthy of standing alongside Cameron's films or even Jonathan Mostow's.

The funny thing is, it's not really a bad cyborg wondering about his humanity in a post-apocalyptic future movie; remove the brand name and stop trying to force it into the Terminator mythology (which does hurt the story), and there's a potentially fun movie here. Terminator demands more, though.

Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

I've mentioned before that it's not a good idea to see movies out of a sense of obligation, which is why I've consciously started scaling back on feeling the need to catch all the Oscar or Chlotrudis or what have you nominees during the first couple months of the year. Movies shouldn't be homework. Still, I often look at stuff on the Brattle's schedule, and I figure I should see some of this stuff, even if it's not something I'm particularly enthused about. Like a retrospective of François Truffaut, focusing on the Antoine Doinel films.

So, maybe I just wasn't in the mood for The 400 Blows this past weekend. I found myself losing patience early and often, and Doinel often felt like a blank to me. I get that it's a movie about a kid getting into trouble because he's got nobody to focus him, but I also don't get a sense of who he would be or could be otherwise. He makes jumps that don't even seem to make sense by kid logic. The story doesn't end so much as it stops, or so it seems.

On another day, I might have enjoyed The 400 Blows a little more, but I'd walked to and from the Common for Terminator, and wasn't exactly in the mood for something abstract (a smidge less so than usual). Obviously, it's a film that can be dissected and studied, but I don't find myself of a mind to.

Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

I liked Stolen Kisses a little more, though I was glad I didn't see it back-to-back with The 400 Blows. The two star the same actor as the same character, but aren't connected very tightly. It might have worked better if the Brattle was able to show "Antoine et Colette", which was made between the two features and establishes Antoine's tendency to fall for entire families.

This one is a collection of anecdotes, not strongly connected, and while some of them are fairly entertaining, there's also a sense of annoying randomness to it, as if Truffaut had a bunch of events that didn't really gel into a story, but he wanted to film them all. It also established Doinel as the sort of character who annoys the heck out of me, because he seems to succeed without ever doing anything well.

On the other hand, this film does introduce us to the lovely Claude Jade as Christine, who will be the highlight of this film and the next; I found myself wishing we were spending as much time with her as with him

Anyway, I did take a bit of a break from reviewing stuff when I finished the IFFB reviews, using my bus time to finish the first Lensman volume. Triplanetary also included "Masters of Space", and, good gravy... I'd love to see movies or TV made of these stories, because for all E.E. "Doc" Smith could come up with thrilling, cliff-hanging adventure stories, he could not write about people at all. Triplanetary was bearable, in part because it's the 1930s and this is pure pulp and the lurid prose is sincere. It's a total engineer's fantasy, with ideas going form concept to flawless production model in days without management, QA, cost & availability of materials, etc., being an issue. "Masters of Space", though, was written in the sixties, and tries to have soapy elements in it, but everyone is so self-aware that it's maddening. The characters talk about how and why they love each other in this purely rational way that never once rings true, and can we please get back to the ancient astronauts, galaxy-conquering marauders, scientists ascending to near-godhood, and villains intending to use one planet as a bullet to take out another?

Final IFFB update:

22 April 2009 (Wednesday): The Brothers Bloom

23 April 2009 (Thursday): Children of Invention, The Missing Person

24 April 2009 (Friday): Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, In The Loop, Pontypool

25 April 2009 (Saturday): Still Walking, Nollywood Babylon, Lost Son of Havana, Grace

26 April 2009 (Sunday): Herb and Dorothy, Helen, Unmistaken Child, The Escapist

27 April 2009 (Monday): For the Love of Movies, Art & Copy

28 April 2009 (Tuesday): World's Greatest Dad

Finished! Now, to start making reservations and vacation plans for Fantasia. I really need to find some way to get paid to travel the world, going to film festivals and reporting back (c'mon, entertainment websites... just think how much content I could generate for you if I didn't have my day job slowing me down!).

Adoration

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 19 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

I don't think I've seen anything of Atom Egoyan's other than The Sweet Hereafter, and I was young enough then that I missed about half of what was going on. There's some similar themes at play here - survivor's guilt, unhappy families, etc. - but it's never as quietly devastating, and some of the storytelling tools seem... unfair, I guess?

Of course, it's not as if a movie is obligated to play fair, and just because certain things are conventions doesn't mean a specific work has to follow them. So, just because Adoration establishes early on that bits have an unreliable narrator doesn't mean the film can't later on show us an unwitnessed event definitively, especially given how the "unreliable" scenes are shown as being completely untrue. Similarly, a piece of information revealed toward the end seems kind of out of left field, and I found myself sitting there thinking "really? you want to go with that?" It's not a terribly ridiculous coincidence, in retrospect, but when you consider that one of the main themes of this movie is how easy it is to manipulate people with false or incomplete information, it's perhaps not unreasonable to wish the filmmakers did it more artfully.

Also, Egoyan perhaps should have chosen his ending scenes a little more carefully. I didn't come out of the film thinking about media manipulation or prejudice, but about how that kid really did not appreciate the value of nice things. That's a fine violin and phone gone to waste.

Terminator Salvation

* * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

For years, I've been hearing from various sci-fi/film fans about how cool it would be to do a Terminator film that focused on the future war, and I didn't get it. Even when I was younger, I knew a bit about the whole "less is more" thing, and that by giving us small glimpses, James Cameron made it worse than we could imagine. And that was before anybody even considered the idea that there might be a PG-13 Terminator sequel, with the future war a bloodless affair conducted in bright sunlight.

That's part of the problem with Terminator Salvation, a competently made sci-fi action movie with some nice effects and a ridiculously overqualified cast. It leeches the horror out of the idea. In my mind, Skynet never took prisoners - why would they need more than a handful? - and the resistance was always scattered guerrillas, not folks with bunkers and helicopters and the like. They probably weren't as dumb as the characters in this movie could be, but let's be honest - they're really just average sci-fi movie dumb, not recognizing an obvious trap and communicating over frequencies that their enemy could easily eavesdrop on.

The bigger problem is that this movie is conceptually smaller than all the others. All three previous movies hit the audience with the idea that the end was the beginning: It's literally the case for the first and (under-rated) third; they used the time-travel storyline to make the movies closed loops, so that the denouement also happens to be the backstory. The second inverts the idea to suggest that the future was now unpredictable, a wide-open road on which the characters are just now starting their journey. This one is just a disposable side-story, something that happened to John Connor during the part of the story that James Cameron deemed relatively unimportant in The Terminator. It's the stuff of comic book tie-ins, not a story worthy of standing alongside Cameron's films or even Jonathan Mostow's.

The funny thing is, it's not really a bad cyborg wondering about his humanity in a post-apocalyptic future movie; remove the brand name and stop trying to force it into the Terminator mythology (which does hurt the story), and there's a potentially fun movie here. Terminator demands more, though.

Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

I've mentioned before that it's not a good idea to see movies out of a sense of obligation, which is why I've consciously started scaling back on feeling the need to catch all the Oscar or Chlotrudis or what have you nominees during the first couple months of the year. Movies shouldn't be homework. Still, I often look at stuff on the Brattle's schedule, and I figure I should see some of this stuff, even if it's not something I'm particularly enthused about. Like a retrospective of François Truffaut, focusing on the Antoine Doinel films.

So, maybe I just wasn't in the mood for The 400 Blows this past weekend. I found myself losing patience early and often, and Doinel often felt like a blank to me. I get that it's a movie about a kid getting into trouble because he's got nobody to focus him, but I also don't get a sense of who he would be or could be otherwise. He makes jumps that don't even seem to make sense by kid logic. The story doesn't end so much as it stops, or so it seems.

On another day, I might have enjoyed The 400 Blows a little more, but I'd walked to and from the Common for Terminator, and wasn't exactly in the mood for something abstract (a smidge less so than usual). Obviously, it's a film that can be dissected and studied, but I don't find myself of a mind to.

Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 23 May 2009 at AMC Boston Common #1 (first-run)

I liked Stolen Kisses a little more, though I was glad I didn't see it back-to-back with The 400 Blows. The two star the same actor as the same character, but aren't connected very tightly. It might have worked better if the Brattle was able to show "Antoine et Colette", which was made between the two features and establishes Antoine's tendency to fall for entire families.

This one is a collection of anecdotes, not strongly connected, and while some of them are fairly entertaining, there's also a sense of annoying randomness to it, as if Truffaut had a bunch of events that didn't really gel into a story, but he wanted to film them all. It also established Doinel as the sort of character who annoys the heck out of me, because he seems to succeed without ever doing anything well.

On the other hand, this film does introduce us to the lovely Claude Jade as Christine, who will be the highlight of this film and the next; I found myself wishing we were spending as much time with her as with him

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

IFFB 2009 Closing Night: World's Greatest Dad

I think I may have said this at the end of the SXSW postings, but it bears repeating: The end of a film festival is a weird feeling. Or maybe a weird lack of feeling; as much as I can't ever remember feeling like I wished the whole thing was done already before the end, I've also never walked out of the closing night film and said I wished there was more. I've wished I could stay longer at Fantasia, when I was doing half-festivals, but that's a different thing.

Writing up the reviews is a different thing, though. I can't wait to occasionally spend my bus ride home just reading a book, and not feeling like I've got some obligation to review something I was given a pass for.

The last night of IFFB 09 was a lot of fun, though. It was the only night at the Coolidge, the rain (aside from a few very tiny sprinkles) held off while everybody was waiting in the outside line, and Bobcat Goldthwait, as one might expect of a professional funny person, was a massively entertaining guest. His speech is pretty normal now, although bits of his on-the-edge-of-a-breakdown stand-up delivery still appear now and again. I don't know if you'd say he's hit middle age gracefully, but he'll jokingly refer to himself as "grandpa" whenever he hits a point in a story where he, as a guy once considered cool and edgy, seems conservative or behind the times.

Of course, he can still bust out the inappropriate jokes - that's the bread and butter of World's Greatest Dad, after all. Also, during the Q&A, someone asked if a certain character was played by one of the former members of Nirvana, and he said yeah, he told the guy he was making a movie about someone who died and everyone acted like he was smarter and more important than he was... sound like anything you can identify with?

He apologized after that, of course, and didn't even attempt to hide that he was really nervous about the screening. The Coolidge was a favorite theater of his growing up, and this sort of movie must terrify a filmmaker; hit the wrong note and its a disaster. He was genuinely relieved that we laughed in the right places and didn't in the others, and said that he'd called star Robin Williams during the screening to say it was going well. I guess maybe there really is a rich vein of insecurity in most comedians.

For Love of the Movies

* * * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 28 April 2009 at the Coolidge Corner Theater #1 (Independent Film Festival of Boston Closing Night)

World's Greatest Dad is deliciously black comedy, the sort that revels not just in how horrible the characters can be, but also regularly raises that bar by going for absurdity as well. That's not terribly uncommon; lots of filmmakers, comedians, and other creative types have a bunch of mean jokes inside them. What's kind of amazing about this one is that writer/director Bobcat Goldthwait and star Robin Williams manage to create a great deal of empathy for the title character even as he goes so very wrong.

Williams' Lance Clayton dreams not of being a writer, but of being published (he's got multiple rejection slips for each manuscript). In the meantime, he teaches high-school English at the high school his son Kyle (Daryl Sabara) attends, and though the principal has just told him that they'll be dropping his poetry class if enrollment doesn't improve, things aren't all bad. He's got a good thing going with fellow teacher Claire (Alexie Gilmore), and a son who... Well, who quite honestly, is a rude, porn-obsessed jackass. After a night out with Claire, he returns home to find he's lost Kyle. Crushed, and not wanting to face awkward questions, he writes a note to explain; when students respond to it and ask if Kyle had written anything else, Lance fakes a journal. The journal becomes a sensation, and Lance is only too happy to bask in the attention his writing is finally receiving - even if Kyle's best friend Andrew (Evan Martin) questions whether a slow, pervy tool like Kyle could possibly have written it.

Over the course of his career, Robin Williams's most notable roles have been extreme types: He's best known for hyperactive, motormouthed characters in movies that slather the sentiment on with a ladle, but has enough against-type, creepy parts that you can't mention the first without the latter. Here, he finds an unusually good balance between the two. Lance is quick-witted and frequently funny, but never gets so into it that the audience just dismisses it as Williams doing his shtick, but he's also unnerving as he goes down a path that is maybe not quite dark, in the traditional sense, but certainly questionable. The result is that he convinces us that a series of choices that immediately seem wrong also seem, given this situation and this character, reasonable. He's a believable guy amid a fair amount of unbelievable situations.

Complete review at eFilmCritic, along with one other review.

Writing up the reviews is a different thing, though. I can't wait to occasionally spend my bus ride home just reading a book, and not feeling like I've got some obligation to review something I was given a pass for.

The last night of IFFB 09 was a lot of fun, though. It was the only night at the Coolidge, the rain (aside from a few very tiny sprinkles) held off while everybody was waiting in the outside line, and Bobcat Goldthwait, as one might expect of a professional funny person, was a massively entertaining guest. His speech is pretty normal now, although bits of his on-the-edge-of-a-breakdown stand-up delivery still appear now and again. I don't know if you'd say he's hit middle age gracefully, but he'll jokingly refer to himself as "grandpa" whenever he hits a point in a story where he, as a guy once considered cool and edgy, seems conservative or behind the times.

Of course, he can still bust out the inappropriate jokes - that's the bread and butter of World's Greatest Dad, after all. Also, during the Q&A, someone asked if a certain character was played by one of the former members of Nirvana, and he said yeah, he told the guy he was making a movie about someone who died and everyone acted like he was smarter and more important than he was... sound like anything you can identify with?

He apologized after that, of course, and didn't even attempt to hide that he was really nervous about the screening. The Coolidge was a favorite theater of his growing up, and this sort of movie must terrify a filmmaker; hit the wrong note and its a disaster. He was genuinely relieved that we laughed in the right places and didn't in the others, and said that he'd called star Robin Williams during the screening to say it was going well. I guess maybe there really is a rich vein of insecurity in most comedians.

For Love of the Movies

* * * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 28 April 2009 at the Coolidge Corner Theater #1 (Independent Film Festival of Boston Closing Night)

World's Greatest Dad is deliciously black comedy, the sort that revels not just in how horrible the characters can be, but also regularly raises that bar by going for absurdity as well. That's not terribly uncommon; lots of filmmakers, comedians, and other creative types have a bunch of mean jokes inside them. What's kind of amazing about this one is that writer/director Bobcat Goldthwait and star Robin Williams manage to create a great deal of empathy for the title character even as he goes so very wrong.

Williams' Lance Clayton dreams not of being a writer, but of being published (he's got multiple rejection slips for each manuscript). In the meantime, he teaches high-school English at the high school his son Kyle (Daryl Sabara) attends, and though the principal has just told him that they'll be dropping his poetry class if enrollment doesn't improve, things aren't all bad. He's got a good thing going with fellow teacher Claire (Alexie Gilmore), and a son who... Well, who quite honestly, is a rude, porn-obsessed jackass. After a night out with Claire, he returns home to find he's lost Kyle. Crushed, and not wanting to face awkward questions, he writes a note to explain; when students respond to it and ask if Kyle had written anything else, Lance fakes a journal. The journal becomes a sensation, and Lance is only too happy to bask in the attention his writing is finally receiving - even if Kyle's best friend Andrew (Evan Martin) questions whether a slow, pervy tool like Kyle could possibly have written it.

Over the course of his career, Robin Williams's most notable roles have been extreme types: He's best known for hyperactive, motormouthed characters in movies that slather the sentiment on with a ladle, but has enough against-type, creepy parts that you can't mention the first without the latter. Here, he finds an unusually good balance between the two. Lance is quick-witted and frequently funny, but never gets so into it that the audience just dismisses it as Williams doing his shtick, but he's also unnerving as he goes down a path that is maybe not quite dark, in the traditional sense, but certainly questionable. The result is that he convinces us that a series of choices that immediately seem wrong also seem, given this situation and this character, reasonable. He's a believable guy amid a fair amount of unbelievable situations.

Complete review at eFilmCritic, along with one other review.

Monday, May 18, 2009

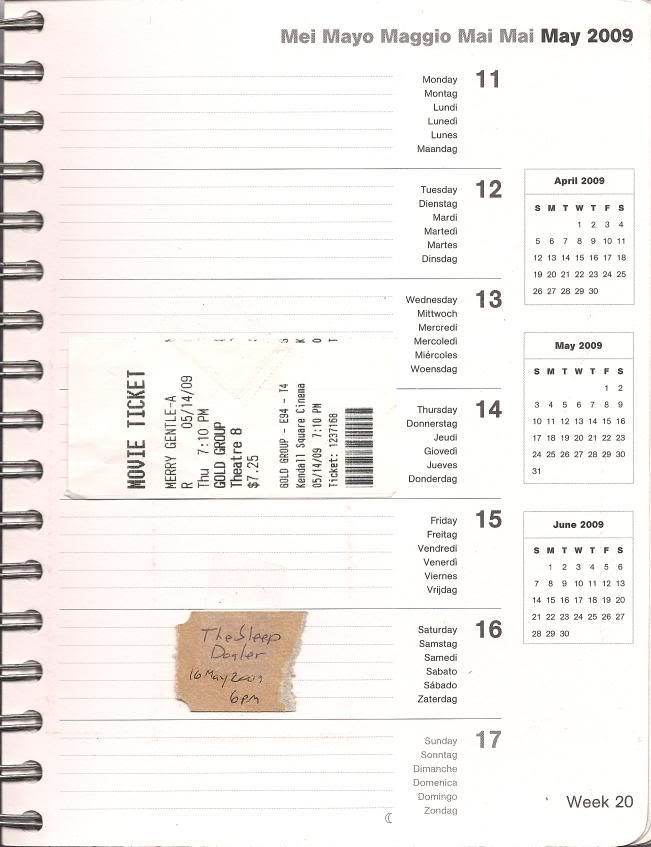

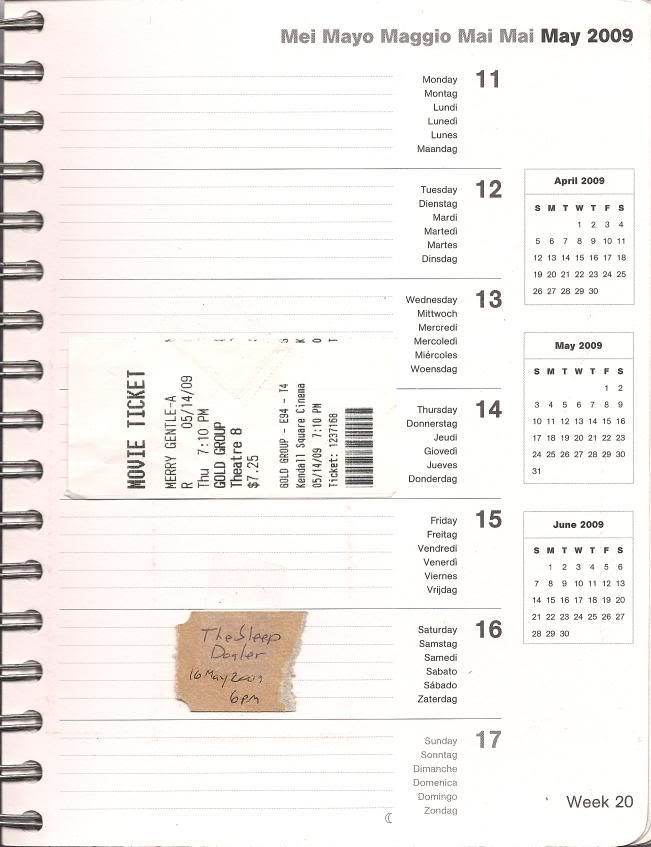

This Week In Tickets: 11 May 2009 to 17 May 2009

West coast baseball just messes things up in every way possible. You stay up until 1am, get to work a little late, leading to staying a little late, and even if there is time to catch a movie after, you're kind of dragging, so, repeat. Then plans get messed up by print problems, leading to something this sparse:

Aside from baseball, it was a pretty uninspiring week for new releases - just Angels & Demons at the multiplexes, and good gravy no. Aside from how much The Da Vinci Code bored me, I really don't get the trailer: Tom Hanks is playing the hero, right? And the backstory is that the Catholic Church did terribly things to the scientists of the Illuminati, who are now striking back. So, why's Hanks working for the Church in this one? Wouldn't his sympathies naturally be with the Illuminati? Or is it about grudge-holding being bad?

The stuff at the boutique houses was a little more inspiring, but not enough to get me to go. I'll see Adoration with the usual group this Tuesday, but otherwise was only really drawn to The Merry Gentleman, and that on the basis of "Michael Keaton! I like that guy! What's he been up to since that White Noise debacle... Oh, directing? That's interesting." It had a one-week run at the Kendall and I'll come back and review it anyway, because there's nothing on HBS/EFC, and seeing a Keaton movie pass unnoticed makes me a bit sad.

This weeks IFFB update:

22 April 2009 (Wednesday): The Brothers Bloom

23 April 2009 (Thursday): Children of Invention, The Missing Person

24 April 2009 (Friday): Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, In The Loop, Pontypool

25 April 2009 (Saturday): Still Walking, Nollywood Babylon, Lost Son of Havana, Grace

26 April 2009 (Sunday): Herb and Dorothy, Helen, Unmistaken Child, The Escapist

27 April 2009 (Monday): For the Love of Movies, Art & Copy

28 April 2009 (Tuesday): World's Greatest Dad

I'll finish writing up World's Greatest Dad sometime in the next couple of days and then festival crunch will be over... Well, at least until NYAFF or Fantasia.

The Merry Gentleman

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 14 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

I wanted to like The Merry Gentleman more than I did; its two leads are folks I really like and Michael Keaton, in particular, seems to deserve a comeback. Sad to say, this morose movie isn't going to be it. Keaton seems to go overboard reigning his natural infectious energy in, and while being cheerful wouldn't have been appropriate for this character, his Frank Logan is so deliberately dour as to raise suspicion, especially considering the artificially long time before we hear him speak.

Maybe he just can't judge his own performance while directing, because much of the rest of the movie is quite good. Kelly Macdonald, for instance, is absolutely fantastic as Kate Frazier, a battered wife who has fled halfway across the country, and he does nice things with Ron Lazzeretti's screenplay. I liked the little choices it made, like everything involving Kate's Christmas tree, and some of the cinematography is just fantastic. I wished the hitman stuff had been given a little more background - as much as the movie needs Kate involved with something violent, the movie seems to take this sort of activity for granted.

Still, it's nice to see Keaton dong something interesting. I didn't love A Shot at Glory or Game 6, but they're worth seeing, and better than all the crud or The Dad Roles he's been playing around them.

Aside from baseball, it was a pretty uninspiring week for new releases - just Angels & Demons at the multiplexes, and good gravy no. Aside from how much The Da Vinci Code bored me, I really don't get the trailer: Tom Hanks is playing the hero, right? And the backstory is that the Catholic Church did terribly things to the scientists of the Illuminati, who are now striking back. So, why's Hanks working for the Church in this one? Wouldn't his sympathies naturally be with the Illuminati? Or is it about grudge-holding being bad?

The stuff at the boutique houses was a little more inspiring, but not enough to get me to go. I'll see Adoration with the usual group this Tuesday, but otherwise was only really drawn to The Merry Gentleman, and that on the basis of "Michael Keaton! I like that guy! What's he been up to since that White Noise debacle... Oh, directing? That's interesting." It had a one-week run at the Kendall and I'll come back and review it anyway, because there's nothing on HBS/EFC, and seeing a Keaton movie pass unnoticed makes me a bit sad.

This weeks IFFB update:

22 April 2009 (Wednesday): The Brothers Bloom

23 April 2009 (Thursday): Children of Invention, The Missing Person

24 April 2009 (Friday): Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, In The Loop, Pontypool

25 April 2009 (Saturday): Still Walking, Nollywood Babylon, Lost Son of Havana, Grace

26 April 2009 (Sunday): Herb and Dorothy, Helen, Unmistaken Child, The Escapist

27 April 2009 (Monday): For the Love of Movies, Art & Copy

28 April 2009 (Tuesday): World's Greatest Dad

I'll finish writing up World's Greatest Dad sometime in the next couple of days and then festival crunch will be over... Well, at least until NYAFF or Fantasia.

The Merry Gentleman

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 14 May 2009 at Landmark Kendall Square #8 (first-run)

I wanted to like The Merry Gentleman more than I did; its two leads are folks I really like and Michael Keaton, in particular, seems to deserve a comeback. Sad to say, this morose movie isn't going to be it. Keaton seems to go overboard reigning his natural infectious energy in, and while being cheerful wouldn't have been appropriate for this character, his Frank Logan is so deliberately dour as to raise suspicion, especially considering the artificially long time before we hear him speak.

Maybe he just can't judge his own performance while directing, because much of the rest of the movie is quite good. Kelly Macdonald, for instance, is absolutely fantastic as Kate Frazier, a battered wife who has fled halfway across the country, and he does nice things with Ron Lazzeretti's screenplay. I liked the little choices it made, like everything involving Kate's Christmas tree, and some of the cinematography is just fantastic. I wished the hitman stuff had been given a little more background - as much as the movie needs Kate involved with something violent, the movie seems to take this sort of activity for granted.

Still, it's nice to see Keaton dong something interesting. I didn't love A Shot at Glory or Game 6, but they're worth seeing, and better than all the crud or The Dad Roles he's been playing around them.

IFFB 2009 Day Six: For Love of the Movies and Art & Copy

Monday was the second-to-last day of the festival, and took place at the ICA. In previous years, the festival would show a full slate of films on this day, but the organizers felt that this was spreading everything too thin - both the staff and the attendees. I admit, I've run myself ragged going between Somerville, Cambridge, and Brookline in previous years, but I also would have liked some other choices on Monday night, even if it was just repeats from earlier in the festival.

The two movies I did see weren't bad, and they made for an interesting double feature: Both film criticism and advertising are about an attempt to be creative and memorable with a specific purpose in mind. Both had a good number of clips, a history lesson, and plentiful interviews with the folks who do it for a living. I think Art & Copy winds up the better movie, as it doesn't have so many obvious biases and doesn't seem like quite so obvious a lecture.

An entertaining part of Doug Pray's Q&A after Art & Copy (the one for Peary's For the Love of Movies was mostly his friends telling him how wonderful he/his film was) was Pray getting excited about the theater he was showing it in, and I have to agree - the ICA theater is a pretty amazing space. The screen is lowered into the middle of a stage area, and the stage not only has curtains at the front, but at the back; when opened, they give a fantastic view of the harbor. Even if you take it as a multi-purpose room, I'm not sure exactly what purpose it serves.

But I love it. Aside from just being a beautiful space, there's something delightful about the way that the thin screen which you can see behind from certain angles reminds the audience of the projection mechanism. In most theaters, your mind can process the screen as a window; a television is a box that has things in it. At the ICA, your movie is just hanging in mid-air, like a special effect, a spell that a wizard has cast to see something far away. Some may take seeing the edges of the illusion so clearly as spoiling the magic of the movies, but I must admit, I kind of like it.

For Love of the Movies

* * ½ (out of four)

Seen 27 April 2009 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (Independent Film Festival of Boston)

For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism takes on a century of its subject in less than ninety minutes, and as is almost inevitable, feels a little uneven. There are places where seems to do little more than scratch the surface, and even when filmmaker Geary Peary does dig a little deeper, it often doesn't seem deep enough. Whether this means the movie should have had a tighter focus on some specific thread or been expanded (and then, perhaps, broken into six half-hour chunks, as a PBS series), I'm not sure.

Aside from being a film critic for the Boston Phoenix, Peary is also a college professor, and he structures his film like a college course. "Dawn (1907-1929)" focuses on the early days of cinema, with particular attention paid to Frank E. Woods, the first critic of note who went on to co-write Birth of a Nation. "Cult Critics and Crowther (1930-1953)" shows film reviewing evolving into the form we recognize today, with star ratings and the championing of worthy independent and foreign films. "Auteurism and After (1954-1967)" introduces us to the rivalry between Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, which carries over into "When Criticism Mattered (1968-1980). That time period overlaps with "TV, Fans, and Videotape (1975-1995)", which covers the rise of the fanzine. Finally, the film finishes up with "Digital Rebellion (1996+)".

With a scant ten or fifteen minutes with which to cover each of these segments, there's some limitations on what Peary can include. Some are right up there in the title - this is the story of American film criticism, so the groundbreaking work being done in France is mostly excluded, except in terms of how it pitted Sarris and Kael against each other. Perhaps a more subtle selection bias is how much time is how focused the film is on newspapers' reviews of new releases. Criticism that emerges from academia gets very short shrift, and while "TV, Fans, and Videotape" mentions Siskel & Ebert and how video led to the revisiting of older films by enthusiasts as much as professionals, it doesn't do much more than that, even though these are factors which would have a major influence on the film's concluding chapter.

Complete review at eFilmCritic.

Art & Copy

* * * (out of four)

Seen 27 April 2009 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (Independent Film Festival of Boston)

If there's high art and low art, advertising must be considered the lowest of them, with perhaps only grudging admission that any part of it can be considered art at all. Advertising is creative work, though, and for better or worse, a good ad probably has a much larger impact than a good piece of non-commercial artwork.

Director Doug Pray's Art & Copy focuses on the good ads, whether you measure that by artistic merit or commercial success. Those looking for an examination of the rightness and wrongness of pervasive advertising as a phenomenon should look elsewhere; this is an overview of how the medium works combined with a look at some of its more noteworthy practitioners. A key example of both comes early, as we're told about Bill Bernbach, who changed the face of advertising by putting the art director and copywriter in the same room. Before this, ads were very text-heavy, a far cry form the punchy, slickly-designed ads of today.

We get insight on some of the simpler, and most pervasive, advertising campaigns of recent years. Jeff Goodby and Rich Silverstein, who describe their job as "entertaining society using clients' products" talk about their "got milk?" campaign, pointing out how the much-imitated catchphrase was originally the punchline to a very elaborate commercial, while also breaking down how it evolved from the client's specific needs. Pray also talks to Dan Wieden, who came up with "Just Do It". His stories are less about how they built the campaign (although the inspiration for the phrase is amusing), and more about how it took on a life of its own.

Complete review at eFilmCritic.

The two movies I did see weren't bad, and they made for an interesting double feature: Both film criticism and advertising are about an attempt to be creative and memorable with a specific purpose in mind. Both had a good number of clips, a history lesson, and plentiful interviews with the folks who do it for a living. I think Art & Copy winds up the better movie, as it doesn't have so many obvious biases and doesn't seem like quite so obvious a lecture.

An entertaining part of Doug Pray's Q&A after Art & Copy (the one for Peary's For the Love of Movies was mostly his friends telling him how wonderful he/his film was) was Pray getting excited about the theater he was showing it in, and I have to agree - the ICA theater is a pretty amazing space. The screen is lowered into the middle of a stage area, and the stage not only has curtains at the front, but at the back; when opened, they give a fantastic view of the harbor. Even if you take it as a multi-purpose room, I'm not sure exactly what purpose it serves.

But I love it. Aside from just being a beautiful space, there's something delightful about the way that the thin screen which you can see behind from certain angles reminds the audience of the projection mechanism. In most theaters, your mind can process the screen as a window; a television is a box that has things in it. At the ICA, your movie is just hanging in mid-air, like a special effect, a spell that a wizard has cast to see something far away. Some may take seeing the edges of the illusion so clearly as spoiling the magic of the movies, but I must admit, I kind of like it.

For Love of the Movies

* * ½ (out of four)

Seen 27 April 2009 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (Independent Film Festival of Boston)

For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism takes on a century of its subject in less than ninety minutes, and as is almost inevitable, feels a little uneven. There are places where seems to do little more than scratch the surface, and even when filmmaker Geary Peary does dig a little deeper, it often doesn't seem deep enough. Whether this means the movie should have had a tighter focus on some specific thread or been expanded (and then, perhaps, broken into six half-hour chunks, as a PBS series), I'm not sure.

Aside from being a film critic for the Boston Phoenix, Peary is also a college professor, and he structures his film like a college course. "Dawn (1907-1929)" focuses on the early days of cinema, with particular attention paid to Frank E. Woods, the first critic of note who went on to co-write Birth of a Nation. "Cult Critics and Crowther (1930-1953)" shows film reviewing evolving into the form we recognize today, with star ratings and the championing of worthy independent and foreign films. "Auteurism and After (1954-1967)" introduces us to the rivalry between Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, which carries over into "When Criticism Mattered (1968-1980). That time period overlaps with "TV, Fans, and Videotape (1975-1995)", which covers the rise of the fanzine. Finally, the film finishes up with "Digital Rebellion (1996+)".

With a scant ten or fifteen minutes with which to cover each of these segments, there's some limitations on what Peary can include. Some are right up there in the title - this is the story of American film criticism, so the groundbreaking work being done in France is mostly excluded, except in terms of how it pitted Sarris and Kael against each other. Perhaps a more subtle selection bias is how much time is how focused the film is on newspapers' reviews of new releases. Criticism that emerges from academia gets very short shrift, and while "TV, Fans, and Videotape" mentions Siskel & Ebert and how video led to the revisiting of older films by enthusiasts as much as professionals, it doesn't do much more than that, even though these are factors which would have a major influence on the film's concluding chapter.

Complete review at eFilmCritic.

Art & Copy

* * * (out of four)

Seen 27 April 2009 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (Independent Film Festival of Boston)

If there's high art and low art, advertising must be considered the lowest of them, with perhaps only grudging admission that any part of it can be considered art at all. Advertising is creative work, though, and for better or worse, a good ad probably has a much larger impact than a good piece of non-commercial artwork.

Director Doug Pray's Art & Copy focuses on the good ads, whether you measure that by artistic merit or commercial success. Those looking for an examination of the rightness and wrongness of pervasive advertising as a phenomenon should look elsewhere; this is an overview of how the medium works combined with a look at some of its more noteworthy practitioners. A key example of both comes early, as we're told about Bill Bernbach, who changed the face of advertising by putting the art director and copywriter in the same room. Before this, ads were very text-heavy, a far cry form the punchy, slickly-designed ads of today.

We get insight on some of the simpler, and most pervasive, advertising campaigns of recent years. Jeff Goodby and Rich Silverstein, who describe their job as "entertaining society using clients' products" talk about their "got milk?" campaign, pointing out how the much-imitated catchphrase was originally the punchline to a very elaborate commercial, while also breaking down how it evolved from the client's specific needs. Pray also talks to Dan Wieden, who came up with "Just Do It". His stories are less about how they built the campaign (although the inspiration for the phrase is amusing), and more about how it took on a life of its own.

Complete review at eFilmCritic.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Sleep Dealer

Strange things happen with small films from small distributors. I intended to see this Friday night, but when I got to the ticket counter, was told the theater had gotten a bad print; the subtitles from reel 2 were duplicated on reel 4, which could make the movie rough going if you don't speak Spanish. Rough deal for the theater, I imagine: Not only does this kill Friday night, but who knows how many folks come back, even though they said a corrected print would be in Saturday morning? Heck, the loss of word-of-mouth must hurt.

I did come back Saturday afternoon, though, and quite enjoyed the film. It's the sort of thing I get really excited about seeing in Montreal every summer, an odd little sci-fi film from a relatively unexpected place, so getting to see it in a theater near home is a treat.

Sleep Dealer

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 16 May 2009 at the Brattle Theater (Special Engagement)

Science fiction on film is tricky. The money to do spectacle generally comes with strings attached, but without it, a filmmaker runs the risk of having their world look unconvincing or settling for using their big ideas to tell a small story. Alex Rivera's Sleep Dealer has managed to scrape together enough to have some scope even as it tells a ground-level story.

Memo Cruz (Luis Fernando Peña) starts out on his father's farm in Santa Ana del Rio, Oaxaca, Mexico. It used to be impressive, but now it's marginal; an American company has dammed the nearby river and the Cruzes are forced to buy their water from the reservoir. When Memo's ham radio is mistaken for a terrorist spy, he heads north to Tijuana, intending to find work tele-operating robots in wealthier nations. Along the way, he meets Luz (Leonor Varela), a writer whose blog entries are commentary on her memories uploaded directly to the net. Not many people are buying, although her entries on Memo have attracted the attention of Rudolfoz "Rudy" Rodriguez (Jacob Vargas), who, ironically, teleoperates weaponry in Mexico from San Diego.

If there's a theme to the future of Sleep Dealer, it's that the more things change, the more they stay the same, at least for poor countries like Mexico; the indignities just creep in closer. America dams the rivers and then sells locals their own water back at inflated prices, and now they can get cheap Mexican labor and still have the border locked down tight (the film's title is the term for the warehouses along the border where low-paid workers manipulate robots around the world, despite the toll so much VR takes on their bodies and eyesight). If you thought Cops was exploitative, wait until you see Drones.

That's an earnedly cynical view of the future, and that's before getting to the Matrix-style nodes the characters have implanted in their bodies for interfacing with the net. As creepy as the pods in The Matrix were, there's something even more uncaring about the sleep factories, as the workers stand for hours on end, wearing oxygen masks to keep them alert and milky contact lenses. It's not an anti-technology movie, though - although there are slight hints of body horror as we're introduced to the nodes, it's mostly treated as an ethically neutral technology: A little unsettling at first, but fascinating and useful. Those spots of silver are our main reminder that we're in the future, but there's a lot of nice details that establish the period while also sneaking in the occasional bit of satire.

It's good that Rivera's setting gives the audience a fair amount of food for thought, because the story is kind of lightweight. The cast does well enough by the characters, never pulling the audience out of the movie. There are straightforward parallels in the guilt both Memo and Rudy feel over what happens in the first half of the movie as well as how they each work in the other's country without crossing the border. I do like how Rivera winds up kick-starting the story out of something that had been introduced as black comedy, and though the end is a bit contrived, it's enough fun that I wish there had been a little more room in the effects budget for it. The effects themselves are actually pretty decent - it's impressive what can be done on a small budget these days, so long as the director chooses his spots right, which Rivera, by and large, does.

Rivera's put together a nice science fiction story here, from a perspective not frequently seen in the genre, at least on film. Sleep Dealer is both good speculation and allegory, well worth seeking out for those interested in science fiction that does more than overpower them.

Also at HBS.

I did come back Saturday afternoon, though, and quite enjoyed the film. It's the sort of thing I get really excited about seeing in Montreal every summer, an odd little sci-fi film from a relatively unexpected place, so getting to see it in a theater near home is a treat.

Sleep Dealer

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 16 May 2009 at the Brattle Theater (Special Engagement)

Science fiction on film is tricky. The money to do spectacle generally comes with strings attached, but without it, a filmmaker runs the risk of having their world look unconvincing or settling for using their big ideas to tell a small story. Alex Rivera's Sleep Dealer has managed to scrape together enough to have some scope even as it tells a ground-level story.

Memo Cruz (Luis Fernando Peña) starts out on his father's farm in Santa Ana del Rio, Oaxaca, Mexico. It used to be impressive, but now it's marginal; an American company has dammed the nearby river and the Cruzes are forced to buy their water from the reservoir. When Memo's ham radio is mistaken for a terrorist spy, he heads north to Tijuana, intending to find work tele-operating robots in wealthier nations. Along the way, he meets Luz (Leonor Varela), a writer whose blog entries are commentary on her memories uploaded directly to the net. Not many people are buying, although her entries on Memo have attracted the attention of Rudolfoz "Rudy" Rodriguez (Jacob Vargas), who, ironically, teleoperates weaponry in Mexico from San Diego.

If there's a theme to the future of Sleep Dealer, it's that the more things change, the more they stay the same, at least for poor countries like Mexico; the indignities just creep in closer. America dams the rivers and then sells locals their own water back at inflated prices, and now they can get cheap Mexican labor and still have the border locked down tight (the film's title is the term for the warehouses along the border where low-paid workers manipulate robots around the world, despite the toll so much VR takes on their bodies and eyesight). If you thought Cops was exploitative, wait until you see Drones.

That's an earnedly cynical view of the future, and that's before getting to the Matrix-style nodes the characters have implanted in their bodies for interfacing with the net. As creepy as the pods in The Matrix were, there's something even more uncaring about the sleep factories, as the workers stand for hours on end, wearing oxygen masks to keep them alert and milky contact lenses. It's not an anti-technology movie, though - although there are slight hints of body horror as we're introduced to the nodes, it's mostly treated as an ethically neutral technology: A little unsettling at first, but fascinating and useful. Those spots of silver are our main reminder that we're in the future, but there's a lot of nice details that establish the period while also sneaking in the occasional bit of satire.

It's good that Rivera's setting gives the audience a fair amount of food for thought, because the story is kind of lightweight. The cast does well enough by the characters, never pulling the audience out of the movie. There are straightforward parallels in the guilt both Memo and Rudy feel over what happens in the first half of the movie as well as how they each work in the other's country without crossing the border. I do like how Rivera winds up kick-starting the story out of something that had been introduced as black comedy, and though the end is a bit contrived, it's enough fun that I wish there had been a little more room in the effects budget for it. The effects themselves are actually pretty decent - it's impressive what can be done on a small budget these days, so long as the director chooses his spots right, which Rivera, by and large, does.

Rivera's put together a nice science fiction story here, from a perspective not frequently seen in the genre, at least on film. Sleep Dealer is both good speculation and allegory, well worth seeking out for those interested in science fiction that does more than overpower them.

Also at HBS.

Thursday, May 14, 2009

Star Trek

It's true - I've wanted something like this for something like fifteen years. There's likely no way to prove it, unless Google has archived message board archives from the early nineties from Portland, Maine area BBSes on whatever pre-dated newsgroups. Please don't go look for them - I was a teenager typing on a 64K Atari 800XL with a 1200-baud modem. My argument at the time was that it would have been a crying shame if Hamlet had died with Richard Burbage, but apparently the franchise had to go dormant before Paramount would consider giving it the fresh coat of paint.

I have to admit, I was kind of surprised to show up at the comic shop on Wednesday and find that the other folks there who had seen it over the weekend were disappointed, especially after hearing how stoked my brother and his girlfriend had been (they saw it at a regular cineplex after missing the train to the furniture store). The easy response is that this is to be expected and maybe a good thing - if the mainstream audience digs it, it doesn't matter what a bunch of bitter nerds think. The Picnic's clientele isn't all bitter nerds, though, and I'll readily admit - their complaints about the script were things I would normally rip into and then get pissed when someone told me to just turn my brain off and enjoy the ride.