No 2021.08? Well, what can I say, 2021's weird - not much marked as "Day 08" for Fantasia that I caught, and then it was off to the Big Apple!

So, this would have seemed like a bigger deal if I were posting these updates in a timely fashion, what with having gone twice as far since, but even vaccinated for three months in mid-August, I did a lot of hemming and hawing about whether I wanted to get in a metal tube, travel four hours to New York City, and then sit in theaters for a few hours a day before getting into another tube and going home. I don't know as it's actually a lot safer now as I write this in mid-October, but at the very least, I've clearly made my peace with it.

The bulk of the New York Asian Film Festival's activity this year was at the School of Visual Arts Theatre, a nice spot in Manhattan that near as I can tell had its own strict Covid protocols on top of those of New York State/City, so nothing but water allowed in, meaning no reason to take off your mask. For many of the shows, the room was well below capacity, although I didn't get much of a sense of how much that was the venue/festival limiting tickets and how much was the audience not being ready to show up. I don't really know any of the people behind NYAFF now that it's not associated with Subway Cinema, so it could be either.

For all the nervousness at the start, though, it was kind of great. I've mentioned on the blog a few times that I haven't watched nearly as much as I thought I would since getting back from vacation last March, even though I had a bunch of unwatched discs on my shelf and the backlog has only grown over time, but both decision paralysis at the sheer number of options, but by it being just less fun at home than in the theater. Getting back to a theater, with a curated slate and a bunch of people who like the same thing was a lot more fun than I thought it was going to be.

Plus…

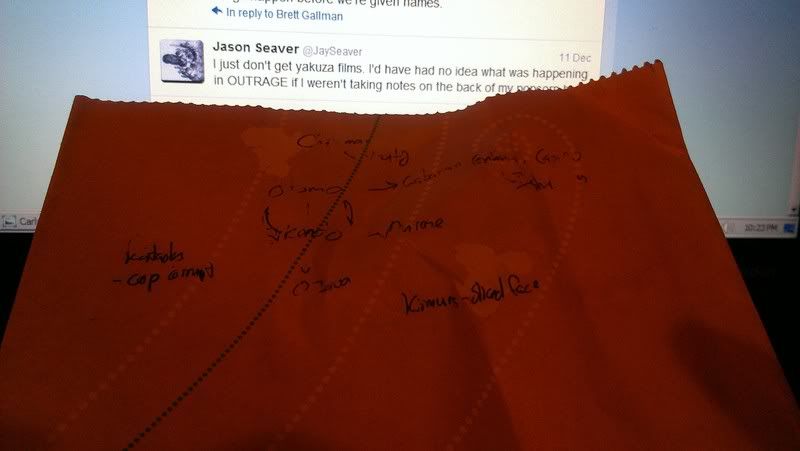

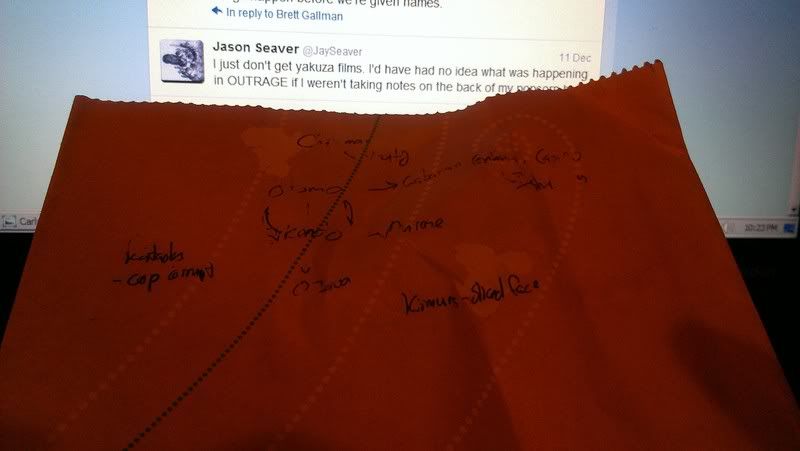

Filmmaker Q&As! Friday's late show had director Oudai Kojima, co-star/producer Jin-Cheol Kim, and moderator Karen Severns there for Joint. Kojima grew up in New York but works in Japan, so this was coming home for him. The thing he was most excited about was his star, Ikken Yamamoto, who from what I gather didn't have many professional credits before this, but he was the sort of guy where you could see the charisma immediately and where there's a certain amount of real-life experience that a lot of professional actors don't have. He also talked about how he wasn't really influenced by a lot of yakuza films, and while I didn't necessarily see that as the case at the time - it sure feels like one in structure - I see where he's coming from now. It's a movie about data mining, replacing employees with contractors, and corporate consolidation at its heart. Truth be told, most yakuza movies have an interest in legitimate business, either as a target or a metaphor, and I kind of feel like Joint might have worked better if it did that more explicitly.

It's also pretty darn stylish, especially for a micro-indie-type thing. You can see the places where it's stretched thin, but it kind of transforms into a look and atmosphere, which you can't exactly do on purpose or even necessarily a second time once you get some attention, but it will be interesting to see what this team can do when they've got some more resources behind them.

The Asian Angel

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 13 August 2021 in SVA Theatre Beatrice (New York Asian Film Festival 2021, DCP)

The Asian Angel is almost, but not quite, two road movies in different languages that got stuck together and tangled up, which occasionally plays into how sometimes people need to get things out even when the idea of people hearing and understanding is awful. That there's a romance involved is unlikely, but the filmmakers fundamentally understand how rickety the whole thing is, and make no apologies for giving the audience the movie they came to see.

It involves widowed novelist Takeshi Aoki (Sosuke Ikematsu) arriving in Seoul with son Manabu (Ryo Sato) in tow despite neither of them speaking Korean and general tension between the countries as bad as they've been in decades, if not since World War II. Takeshi's brother Toru (Joe Odagiri) has been there a while, running a shading import/export business and giving Takeshi the impression that there's work and Japanese-language schools they can afford which may not be the actual case. Nearby, the Choi family has their own tensions; Seol ("Moon" Choi Hee-Seo) is seeing the last vestiges of her hopes to become a pop singer vanish, brother Jung-Woo (Kim Min-Jae) isn't really doing well with the family business that their parents left him, and just-past-teenage sister Po-Mu (Kim Ye-Eun) is bitter that there's not a lot left for her as a result. Their paths have already crossed a couple of times before they're on the same train - the Aokis chasing a deal that might save Toru's business, the Chois visiting their parents' grave - but Manabu's tendency to wander off and an encounter with Seol's agent winds up with the two groups thoroughly intermingled.

Writer/director Yuya Ishii tends to build his movies around lingering wounds, at least as far as the ones that have made the North American festival circuit go (which ironically does not include The Great Passage, his biggest hit, which appears more upbeat), and that's the case here: Whatever modest success Takeshi and Seol may have had at the starts of their careers is thoroughly spent, and their brothers' businesses are both a bad break or two from just not being there any more. These families haven't been broken, but don't necessarily have a lot to say to each other at the moment; everything to be said has been said, and while they need each other, Toru doesn't really know what he's got for Takeshi to do and Jung-Woo can't really articulate to Seol why he thinks visiting their parents' graves will help.

Finding themselves thrown together with the other family doesn't seem like it should work - early scenes of Takeshi and Seol talking past each other smartly play out as her recognizing his good intentions as being somewhat patronizing, and between Ishii and actors Sosuke Ikematsu and Choi Hee-Seo, even the subtitle-reading audience has a clear idea of what they understand and what they don't, and when they later discover that each speaks a little English, there's a bit of relief at finally being able to communicate, but also a need to be clear and put effort into their words. There's a sort of paradox to how these people are communicating - there are a lot of scenes where it's just a relief to get something out without or to listen and sympathize without details, but also care to how having to use a foreign language forces one to consider what they think and feel rather than just lean on expectations.

As introspective as that is, the movie and cast are often lively. Takeshi and Seol make an enjoyable pair because her cynical cool plays well against his haplessness, a shared frustration at things not going as they should uniting them. As the brothers, Joe Odagiri and Kim Min-Jae supply contrasting sorts of easygoing charm; Odagiri's Toru is almost convincing in his amoral detachment until his weakness for Korean girls shows up or he has to stand up for his friends and family but doesn't want to make a big deal out of it, the sort of layered performance that is kind of sneakily good because Ishii doesn't let him usurp Ikematsu as the movie's center, while Kim Min-Jae is kind of familiar in presenting Jung-Woo's working-class bluster while making his pride in Seol's talent the sort of genuine that annoys her but doesn't break into cringe for the audience. Kim Ye-Eun feels like she'd have something really interesting to do if this were just the Chois' story - Po-Mu is often sulky and snarky and she clearly resents being a side character even if she doesn't break the fourth wall about it.

Their stories are all mixed up, and it clearly takes a bit of effort to keep them that way. Ishii doesn't necessarily have to work hard to build things up in order to knock them over - there's something impressively well-calibrated about how he handles the line between "we're poor but stable" and "your car breaking down on a cold night is really dangerous" - but he puts the families into a number of small, disposable tricky situations to keep things moving, with the climax a more urgent one rather than something the others were building to. The angel of the title winds up serving as an odd bit of glue, like Takeshi, Seol, and their families need a little something extra to bind them than just a shared situation.

And yet even without it, the two bickering families have been so thoroughly intertwined by the end that imagining their journeys as merely parallel seems impossible, like this was one story from the start. It's an impressive bit of alchemy, even if it does, maybe, take a little extra time for the combined unit to settle and cool.

Full review at eFilmCritic

Joint

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 13 August 2021 in SVA Theatre Beatrice (New York Asian Film Festival 2021, DCP)

Joint is the sort of festival movie you grade on a bit of a curve - it's so thoroughly independent that even the middle-aged star is a complete newcomer and the strains on the filmmakers' resources are easy to see, but there's enough that feels new and unique done well enough that one is glad to have seen it. The film's flaws make themselves plain as it goes along, but it's filled with stuff worth giving a bit of attention.

It opens in somewhat familiar fashion, with yakuza associate Takeshi "Take" Ishigami (Ikken Yamamoto) being released from prison after two years. He takes a job doing construction from a reformed friend, but he's living in a motel until his parole is over and he can go back to Tokyo and his old work compiling lists of potential victims for the network's scammers, sourced in part by Korean immigrant Jung-Hi (Kim Jin-Cheol). It's a bit of a different world than when he went in - the crooks are making their cold calls from moving cars, the gangs are outsourcing more, and the investment he makes in a software start-up to launder his earnings may be his most successful job even if he doesn't really understand any of it.

For all that the director protested that this wasn't particularly influenced by other yakuza films, it nevertheless has a similar feel: From Battles without Honor and Humanity forward, at the very least, these movies have always been businesslike and dense with information; where the best-known films of this genre focus on gang leadership, director Oudai Kojima and writer Ham-R tend to cast their gaze a little lower on the totem pole. The film is pointed in examining how that milieu has changed, but then, these movies have been grappling with these gangs eyeing respectability for decades.

In fact, it arguably sticks too close to gangster tropes as it goes on. This genre has always been reflections of the legitimate world, and there's a neat angle here in how Take is effectively a contractor and the yakuza less the sort of loyal institutions that Japanese companies used to be (director Kojima grew up in New York, and I'm somewhat curious to what extent he's drawing from American versus Japanese experiences). The sharpest and most fascinating element may be how these scam artists and frauds are evolving into and merging with Big Data and venture capital, a new brand of hidden powers whose artificially-intelligent apps are direct correlations to Take's knack for pulling the useful items out of a mass of information. It's a parallel that intrigues but which Kojima and Ham-R can't quite make into a story, only lightly touching on what's going on at the software company and falling back on what's going on at the top of the gang during the last act, which isn't really important relative to what Take's up to.

And the audience is invested in Take, in large part because Ikken Yamamoto is a heck of a find. It's his first credited performance, let alone lead, but he walks through the film with a smile that's not just charming but signals that Take is completely at ease with who and what he is, cheerfully confused when his friend tries to get him to go straight and sitting in on business meetings with this perfect blend of ignorance and second-hand menace. There's an easy three-way chemistry between him, Kim Jin-Cheol and Kim Chang-Bak, work friends who split when it becomes clear just how amoral one is. On top of that, what seems like a side effect of indie film production and dicey continuity - Take's hair and the rest of his look changes between scenes as they're filmed weeks apart - becomes sort of meaningful, as his "legitimate" business takes the fore and he becomes a sort of chameleon even though he's clearly the same guy underneath.

The whole package isn't quite the sum of its best parts, but between Yamamoto and the angle Kojima takes in seeing the yakuza as something more specific than just corporate analogs, I'm hoping that someone with some resources sees Joint and decides to find out what this group can do with a budget, whether it's something along the same lines or not.

Full review at eFilmCritic

Showing posts with label yakuza. Show all posts

Showing posts with label yakuza. Show all posts

Monday, October 11, 2021

Sunday, January 29, 2017

Monster Fest 2016 03: Playground, Prevenge, Dearest Sister, Mondo Yakuza, Free Fire, The Windmill Massacre, etc.

Saturday was the longest day at Monster Fest, just the way it is at some other genre festivals, even without counting the overnight “Cult of Monster” marathon, which I passed on because, hey, my sleep schedule was going to be messed up enough as it was. That and because the rooftop screening looked like a cool thing to do. And while a six-film day is probably more ambitious than was good for me at this festival, they wound up being spaced out so that I could walk around, get some fish & chips, and otherwise keep the blood circulating.

Plus, the choices made for some fun moviegoing experiences:

Here’s the Q&A that followed Dearest Sister. Although my notes don’t include the moderator, that’s director Mattie Do in the center and Matthew Victor Pastor, who directed the short in front of it (“I Am Jupiter I Am the Biggest Planet” to the right. Both were pretty darn good movies, with both directors pretty fierce in talking about how important it was to them that they be of their place (Laos and the Philippines, respectively). It is not always easy shooting a movie there - I’m not sure how much of an industry Laos has at all - and they both talked about how Western outsiders who do so often come across as a bit condescending, especially around the subject of “sexpats” (and, yeah, there’s a portmanteau I never need to hear again).

That lovely gal down front is Wilma The Whippet, and she is the subject of the picture I most regret not getting at a film festival ever. Wilma is not Ms. Do’s dog - though she has two whippets that appeared in her film, bringing them from Laos to Melbourne for the festival would be logistically difficult - but instead belongs to festival founder Neil Foley, and she watched the film with him, from her own seat directly in front of me. She was exceptionally well-behaved, not barking once, even when the other dogs were on screen, and sitting up in apparent attention for the first half before lying down to rest. Exceptionally good dog, and I wish I’d gotten the shot of her sitting in the theater seat before the movie began.

Also, I love the Kickstarter reward you can see on the screen behind the filmmakers.

You know this picture - the cast & crew of the locally-produced film that shows up to the festival en masse. In this case, it’s the makers of Mondo Yakuza, and my terribly handwritten notes indicate that, from left to right, we’re looking at the fight choreographer whose name I didn’t get down, producer Dylan Heath, actor Cris Cochrane, actress Skye Medusa, star/co-writer Kenji Shimada, director Addison Heath, actor/PA Simon Harcourt, PA Bill Clare, a luchador-masked member of the Screaming Meanies (who did the score), cinematographer Jasmine Jakupi, and my notes get worse from there. Clearly, I’m not a journalist who gets paid for this.

As you might expect, with a bunch of friends in the audience and a crazy movie, it was a somewhat chaotic Q&A, although you could get the gist of how this group makes a lot of movies together, grinding them out fast and trying to make each one a little better and more professional. Interestingly, they mentioned Mondo Yakuza has a distribution deal in Japan and they were looking forward to shooting a filmt here.

Finally, here’s the Lido’s rooftop cinema, which is a neat feature to have and a reminder that late November is late spring there. Not late-late spring - it was kind of chilly by 11pm, so I for one was rather grateful that there were blankets on many of these deck chairs - but certainly the part of the year where this was a regular part of the Lido’s schedule.

In some ways, it was kind of like an urban drive-in, right down to the soundtrack being piped out on a radio signal for which attendees were given receivers on the way in. I’ve to to admit, I’m now mildly curious as to which Boston-area places have flat roofs that could make this work, although I don’t know if the novelty is enough to fit it into the schedule (we’ve got a lot of 35mm midnights compared to the Blu-ray used here)

Anyway, it was a fun day that highlights what a neat festival this is. I almost wish I could make it part of my yearly rotation.

Plac zabaw (Playground)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #8 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

There’s a certain bravery to the way films like Playground transgress, although it’s a courage that is perhaps not all it’s cracked up to be: The filmmakers are obliquely saying incendiary things to an audience that is inclined to search for such meaning and likely to agree with that which is being said, after congratulating themselves on enduring something that folks going to the cinema for mere entertainment wouldn’t. It impresses, it reveals a bit more under scrutiny, and yet, I honestly don’t know whether I’d recommend someone see it rather than just tell them about it.

It starts by focusing on Gabrysia (Michalina Swistun), a smart and serious pre-teen in a small Polish town who has decided that today, the last day of school, is the day she’ll ask her classmate Szymek (Nicolas Przygoda) out. Szymek’s a good-looking class-clown type, the sort eleven-year-old girls like, and Gabrysia has everything she needs to do to not get him to blow it off. As the three prepare for school, Szymek has to help out his handicapped father, while his best friend Ozmek (Przemyslaw Balinski) complains about his baby brother. Gabrysia has a plan not to be blown off, although maybe she should be looking elsewhere.

It would be easy to writer/director Bartosz Kowalski to make Gabrysia the clear-cut protagonist of the film facing unfair rejection, but the fact that he doesn’t is kind of interesting: She’s pushy and demanding, not just ready to declare her affection but looking for a way to back Szymek into having to go out with her. When the film shifts to Szymek’s and Ozmek’s point of view, she comes off as snobby and entitled where before she might have just seemed socially odd, full of unevenly-distributed self-confidence. Michalina Swistun is impressive in giving Kowalski what he wants as perspective and circumstances shift - she’s never precocious in a cute, ingratiating way, but there’s nervousness to when she’s trying to be manipulative and sympathetic horror to her being called on it. Gabrysia is maybe not someone the audience is always behind, but she’s always interesting.

Full review on EFC.

Prevenge

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

Given its title, I wonder if the script for Prevenge at one point had a more explicitly sci-fi angle at one point, playing out as something much more in line with The Terminator rather than taking a darker route where, if its murderous mother-to-be earns the audience’s forgiveness, it’s a much more troublesome decision. I’d kind of like to see that movie sometime, but Alice Lowe seems ideally suited for this take, and she sure as heck makes it interesting.

More than most movies, even those films conceived as the filmmaker’s own star vehicle, Prevenge is made by and for Lowe, and specifically at that time of her life: After writing the script, she directed and acted in this film when she was about seven months pregnant. I’m not sure I can recall a movie so built around the lead actress’s pregnancy in quite the way this one is before - even Absentia, if I recall correctly, is more a case of writing it into the script after casting rather than being integral enough that it was more a necessity for the shoot than a challenge - and doing so is admirably ambitious; I’m not sure how many women would deliberately schedule the intense grind of making an independent film for their third trimester. As much as it likely, in some small way, freed Lowe up from having to think about the physical aspects of the performance as opposed to simply playing the Ruth’s personality, she’s a talented enough actress that this particular bit of authenticity likely wasn’t critical.

On the other hand, it does give her instant credibility with an audience often willing to simplify the idea of pregnancy when she goes to dark places. Ruth, see, hears her unborn child’s voice, and it often tells her to kill, because some person or other will eventually do her harm. It’s a brilliant twist on the usual plot of impending motherhood teaching a woman responsibility and self-sacrifice, as what Ruth is facing is not just the loss of independence and personal pleasure - for Ruth, impending motherhood is not just a fear of being unable to measure up to other people (or alternately repeating her own mother’s mistakes), but utter uncertainty that she’s doing the right thing at all. How can someone like her be a decent mother, even if her motives are good? Have all the changes to her body and the hormones affecting her mind made her someone else, who still has all the flaws she started with?

Full review on EFC.

”I am JUPITER I am the BIGGEST PLANET”

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

I’ve approached movies like “I Am Jupiter I Am the Biggest Planet” with some caution over the last few years, ever since Montreal’s Fantasia Festival concluded a FIlipino Cinema program with a hand-biting satire of the middle-class filmmakers there who make what folks call “poverty porn”, so it was good to see that this short film has much more than conspicuous commiseration to recommend it. It uses the slums of Manila and the wealthier people who scoop from there for their own gratification as a backdrop, but does so in the service of a tight story of people becoming dangerous when pushed to the brink.

Filmmaker Matthew Victor Pastor does a lot of clever things here - he introduces the characters at their own pace and lets the audience get to know them by their actions rather than talking themselves up, and he grounds the events in the location without making the film a polemic. There’s a bit of revenge fantasy to the film, and the contrast between realism and imagination is highlighted by the way he presents the film: It’s visually kind of flat and digital, consciously lacking a lot of fussy camerawork, but also very quiet, with what little speech there is presented as intertitles. It’s a fly-on-the-wall movie that is nonetheless very aware of its artifice, and generally uses both effectively.

Nong Hak (Dearest Sister)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

There’s no universal answer to how much attention should be paid to the living compared to the dead when crafting a ghost story, especially when you consider that a good one will do a great job in misdirecting the audience. Dearest Sister, for instance, puts the supernatural so near its center that it can easily look more important than it is, drawing conscious attention away from the more conventional material that it metaphorically extends. That’s kind of its job, and it does so successfully enough that it not making a lot of sense as a plot device can be quite forgivable.

Taking place in Laos, it inverts some of the traditional ways Westerners go about ghost stories. Nok (Amphiaiphun Phommapunya), for instance, heads into the city for her job working as a personal companion rather than to an isolated mansion. She’ll be helping her cousin Ana (Vilouna Phetmany) out where she can, as Ana is losing her sight and her Estonian husband Jakob (Tambet Tuisk) is frequently away on business. Nok is viewed with suspicion in both her new and old homes, with her immediate family thinking she’ll spend her time looking for a white fiance while Ana treats her country cousin as something between family and a servant, which makes the married couple who serve as maid (Manivanh Boulom) and gardener (Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy) even more hostile. It’s not exactly unwarranted, either; when Ana goes into trances and seems to see things from outside the normal world, Nok doesn’t shrink from exploiting those visions.

Nok arrives at Ana’s house quickly, too quickly to come across as a fish out of water, and that seems purposeful: The impression that forms with the audience is somebody between statuses; though she is actually in a pretty good position, she sees herself as potentially downgraded to a servant, and therefore needing to grab hold of the next level up to the extent that she can. Director Mattie Do and writer Christopher Larsen set the situation up in a way that seems so natural that it’s easy to sympathize with Nok even when she’s acting selfishly at first, with Amphaiphun Phommapunya always making sure that the audience sees how much of her can be explained as being young and in a new environment; her initial steps down a bad path come across as her being in over her head, keeping the audience with her enough to be invested in which way she’ll eventually lean.

Full review on EFC.

Mondo Yakuza

* * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

Mondo Yakuza isn’t quite an “amateurs making a movie for themselves and having fun” production with no commercial prospects, but it has that sort of energy, making it a fairly agreeable throwback to old-school grindhouse productions. I imagine that’s especially true if one’s old grindhouse played a lot of Seijun Suzuki, and in attempting to channel that particular Japanese auteur, these Aussie filmmakes have the room to push things pretty far and still not feel like parody, since what inspired them was so insane.

It starts rough, with a Japanese student telling her drug-dealer boyfriend that she doesn’t worry about danger too much, because her brother back home is yakuza and if anything happens to her, well, you know what would happen. The universe apparently sees that as too good a dare to ignore, so soon enough Ichiro Kataki (Kenji Shimada) is arriving in Australia, picking up a bunch of guns, and looking for the punk who killed his sister. That would be Ryan Beckett (Glenn Maynard), a raving thug who will inevitably wind up holed up in the home of his even more insane mother (Elizabeth O’Callaghan) with his at least comparatively sane brother Calvin (Rob Stanfield).

Though it’s got a vengeful yakuza injected into the middle of it, part of what makes this movie fun is that, while it doesn’t quite play as a spoof of contemporary Australian crime movies, it pretty clearly shares a lot of DNA with things like Chopper and Animal Kingdom (and likely dozens of others that didn’t make such a high-profile Pacific crossing), although it’s got the sort of over-the-top violence and characterization that more serious crime movies would pull back on. That’s actually a point in its favor at this budget level; fake blood is cheap to make and, let’s be honest, even if five not-great actors whose characters die gushing blood at regular intervals have the same amount of screen time as one guy with roughly the same talent in another movie, it’s more exciting and less wearing. The criminal day-to-day of the Beckett Boys isn’t particularly memorable, but it doesn’t completely feel like going through the motions, and the cast is at least given expansive personalities to play up rather than hanging blandly around until they can increase the body count. Rob Stanfield, in particular, brings out a lot of very entertaining frustration as the brother righteously angry that the family business, and likely his corpse, is going to get cut to pieces because his brother is a violent idiot.

Full review on EFC.

Free Fire

* * * ¾(out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

Ben Wheatley has accumulated a cult fanbase by making films that strive to cut out the bits that aren’t in some way special, figuring that most people have seen enough movies to fill in the blanks or just go without if it means not seeing one more bloody scene of a local explaining his town’s weird history to the main character just because it’s going to play out later. At times, this gives his movies a thrill of discovery that they might not otherwise have; at its worst, this impulse can make movies like High-Rise seem perplexing and full of weirdos doing things at random. In Free Fire, it makes for a mainstream action movie that just doesn’t mess around, letting a crazy gunfight expand to fill almost the entire running time without making the audience wait around for the good parts.

The action takes place in 1978, where a number of lowlives have gathered in a Boston warehouse, looking to do an arms deal. Ord (Armie Hammer) is looking to buy, Vernon (Sharlto Copley) is looking to sell, and former Fed Justine (Brie Larson) is brokering the deal. Seems easy enough, but the guns Vernon brought aren’t the model Ord was looking for, and one of Vernon’s guys, Harry (Jack Reynor), has a serious beef with Stevo (Sam Riley), one of Ord’s. That would be enough to get people to start shooting, even if a double-cross wasn’t already inevitable.

So they start shooting at each other, and really don’t stop until the movie ends; moments of conversation generally involve the participants hiding behind whatever may provide them cover, speaking sotto voce to the person next to them or yelling across the open space. This doesn’t make it a dumb action movie at all, it turns out - the script by Wheatley and partner Amy Jump is full of tremendously funny bits, nd while they may have a character yell out in the middle that he’s forgotten which side he’s on, the plotting is certainly tighter than they could have gotten away with. As is their tendency, these filmmakers focus on what’s interesting and exciting, understanding that the audience really doesn’t care that much about the lives of these characters outside this room and thus not wasting any time with flashback and the bare minimum on set-up, dropping enough of what a viewer needs to not be jolted out of the film by wondering why that person is doing that thing which doesn’t make sense without killing the momentum.

Full review on EFC.

”Hell of a Day”

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas Rooftop (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

Though there are still a great many fans of post-apocalyptic scenarios, I’ve started to think that, unless the filmmaker has a genuinely creative way to use the situation as a metaphor for something else, I’d much rather see something like “Hell of a Day” than an extended slog through the end of the word: Give the audience a quick rush of gore and horror without giving it the time to get comfortable with what they’re seeing, and have them ready for the main feature within fifteen minutes. At this 15-minute scale, writer/director Evan Hughes can get the job done without the structure starting to feel hollow.

It’s a perfectly simple set-up - an injured girl played by Alexandra Octavia takes structure in an abandoned-looking inn, only to find that, no, she hasn’t left the living dead entirely behind, and trying to find a safe spot puts her in more danger. Hughes does a lot of things right here - the inn is a great setting whether he and the other filmmakers found it in a state of disrepair or dressed it up, dangerous-looking in its decay but also nightmarish for being a public gathering place so clearly bereft of people, for instance, and when things get bloody, he and make-up artist Liz Jenkins do not do things halfway; it’s genuinely gross. Octavia makes the audience believe that she might have the right attitude to react to the situation with the title, hardened and tough from getting through danger, but also weary and exhausted. And while the short doesn’t quite come full circle in the way that its makers seem to be aiming, it’s a nasty little puzzle box that clicks into place at the end.

The action and events of this movie could easily be the background for someone you see for ten minutes or less on The Walking Dead, and maybe that’s a part of what makes it fun - it reminds the viewer that the guys who wind up just being cannon fodder had their own horrific path to get there. It’s not deep, but it’s also not trying to stretch shallow until it looks deep, and that’s something for which a viewer can be grateful.

The Windmill Massacre (aka The Windmill)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas Rooftop (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

There are plenty of horror movies out there that try to do what the guys making The Windmill Massacre do, but in some ways that makes its relatively modest target harder to hit: While so many are trying to stand out from the pack by being consciously aware of the genre’s structure or trying to elevate themselves to something greater, Nick Jongerius and his collaborators just build something that wouldn’t be out of place in a gruesome EC comic book, and while that may preclude it from later being remembered as one of the era’s great, influential horror movies, it works well enough in the present tense.

Meet Julie - no, scratch that, meet Jennifer Harris (Charlotte Beaumont), who fled her native Australia for Europe a few months ago, although the family that hired her as a nanny has just found out about her fake ID. She flees, hopping on the “Happy Holland Tours” bus when it feels like the police are closing in. It looks like a pretty fly-by-night outfit, with a motley crew also departing from Amsterdam to tour the windmills: Jackson (Ben Batt), a soldier with PTSD; Ruby Rousseau (Fiona Hampton), a former model trying to reinvent herself as a photographer; Curt West (Adam Thomas Wright), a kid just taken out of school by his father Douglas (Patrick Baladi) and strangely unable to get his mother on the phone; Nicholas Cooper (Noah Taylor), a former surgeon; Takashi Kido (Tanroh Ishida), a Japanese tourist whose grandmother wanted her ashes spread in the Netherlands; and Abe (Bart Klever), the tour guide. One windmill not on the tour, where a madman ground murder victims rather than grain, is said to just be a legend, although when the bus breaks down and they can’t find cellular service…

Jongerius and his co-writers (Chris W. Mitchell & Suzy Quid) don’t exactly create the next great slasher villain in Miller Hendrik (Kenan Raven); he doesn’t have a great visual hook to define him or the sort of personality that could carry him into a second movie, and while sequel-readiness isn’t necessary in general for horror movies or practical for this one - his murder weapon is not exactly what you’d call portable, so a follow-up would have to be almost a remake with new tourists - it’s often a good way to measure how enthusiastic one is about the villain in the present tense. There’s enough to Hendrik that I suspect the filmmakers could flesh him out a little given the opportunity, but in this movie, he never really seems to come out of the background, even when the Jongerius gets past the point of cutting away just before the thing following someone attacks.

Full review on EFC.

Plus, the choices made for some fun moviegoing experiences:

Here’s the Q&A that followed Dearest Sister. Although my notes don’t include the moderator, that’s director Mattie Do in the center and Matthew Victor Pastor, who directed the short in front of it (“I Am Jupiter I Am the Biggest Planet” to the right. Both were pretty darn good movies, with both directors pretty fierce in talking about how important it was to them that they be of their place (Laos and the Philippines, respectively). It is not always easy shooting a movie there - I’m not sure how much of an industry Laos has at all - and they both talked about how Western outsiders who do so often come across as a bit condescending, especially around the subject of “sexpats” (and, yeah, there’s a portmanteau I never need to hear again).

That lovely gal down front is Wilma The Whippet, and she is the subject of the picture I most regret not getting at a film festival ever. Wilma is not Ms. Do’s dog - though she has two whippets that appeared in her film, bringing them from Laos to Melbourne for the festival would be logistically difficult - but instead belongs to festival founder Neil Foley, and she watched the film with him, from her own seat directly in front of me. She was exceptionally well-behaved, not barking once, even when the other dogs were on screen, and sitting up in apparent attention for the first half before lying down to rest. Exceptionally good dog, and I wish I’d gotten the shot of her sitting in the theater seat before the movie began.

Also, I love the Kickstarter reward you can see on the screen behind the filmmakers.

You know this picture - the cast & crew of the locally-produced film that shows up to the festival en masse. In this case, it’s the makers of Mondo Yakuza, and my terribly handwritten notes indicate that, from left to right, we’re looking at the fight choreographer whose name I didn’t get down, producer Dylan Heath, actor Cris Cochrane, actress Skye Medusa, star/co-writer Kenji Shimada, director Addison Heath, actor/PA Simon Harcourt, PA Bill Clare, a luchador-masked member of the Screaming Meanies (who did the score), cinematographer Jasmine Jakupi, and my notes get worse from there. Clearly, I’m not a journalist who gets paid for this.

As you might expect, with a bunch of friends in the audience and a crazy movie, it was a somewhat chaotic Q&A, although you could get the gist of how this group makes a lot of movies together, grinding them out fast and trying to make each one a little better and more professional. Interestingly, they mentioned Mondo Yakuza has a distribution deal in Japan and they were looking forward to shooting a filmt here.

Finally, here’s the Lido’s rooftop cinema, which is a neat feature to have and a reminder that late November is late spring there. Not late-late spring - it was kind of chilly by 11pm, so I for one was rather grateful that there were blankets on many of these deck chairs - but certainly the part of the year where this was a regular part of the Lido’s schedule.

In some ways, it was kind of like an urban drive-in, right down to the soundtrack being piped out on a radio signal for which attendees were given receivers on the way in. I’ve to to admit, I’m now mildly curious as to which Boston-area places have flat roofs that could make this work, although I don’t know if the novelty is enough to fit it into the schedule (we’ve got a lot of 35mm midnights compared to the Blu-ray used here)

Anyway, it was a fun day that highlights what a neat festival this is. I almost wish I could make it part of my yearly rotation.

Plac zabaw (Playground)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #8 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

There’s a certain bravery to the way films like Playground transgress, although it’s a courage that is perhaps not all it’s cracked up to be: The filmmakers are obliquely saying incendiary things to an audience that is inclined to search for such meaning and likely to agree with that which is being said, after congratulating themselves on enduring something that folks going to the cinema for mere entertainment wouldn’t. It impresses, it reveals a bit more under scrutiny, and yet, I honestly don’t know whether I’d recommend someone see it rather than just tell them about it.

It starts by focusing on Gabrysia (Michalina Swistun), a smart and serious pre-teen in a small Polish town who has decided that today, the last day of school, is the day she’ll ask her classmate Szymek (Nicolas Przygoda) out. Szymek’s a good-looking class-clown type, the sort eleven-year-old girls like, and Gabrysia has everything she needs to do to not get him to blow it off. As the three prepare for school, Szymek has to help out his handicapped father, while his best friend Ozmek (Przemyslaw Balinski) complains about his baby brother. Gabrysia has a plan not to be blown off, although maybe she should be looking elsewhere.

It would be easy to writer/director Bartosz Kowalski to make Gabrysia the clear-cut protagonist of the film facing unfair rejection, but the fact that he doesn’t is kind of interesting: She’s pushy and demanding, not just ready to declare her affection but looking for a way to back Szymek into having to go out with her. When the film shifts to Szymek’s and Ozmek’s point of view, she comes off as snobby and entitled where before she might have just seemed socially odd, full of unevenly-distributed self-confidence. Michalina Swistun is impressive in giving Kowalski what he wants as perspective and circumstances shift - she’s never precocious in a cute, ingratiating way, but there’s nervousness to when she’s trying to be manipulative and sympathetic horror to her being called on it. Gabrysia is maybe not someone the audience is always behind, but she’s always interesting.

Full review on EFC.

Prevenge

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

Given its title, I wonder if the script for Prevenge at one point had a more explicitly sci-fi angle at one point, playing out as something much more in line with The Terminator rather than taking a darker route where, if its murderous mother-to-be earns the audience’s forgiveness, it’s a much more troublesome decision. I’d kind of like to see that movie sometime, but Alice Lowe seems ideally suited for this take, and she sure as heck makes it interesting.

More than most movies, even those films conceived as the filmmaker’s own star vehicle, Prevenge is made by and for Lowe, and specifically at that time of her life: After writing the script, she directed and acted in this film when she was about seven months pregnant. I’m not sure I can recall a movie so built around the lead actress’s pregnancy in quite the way this one is before - even Absentia, if I recall correctly, is more a case of writing it into the script after casting rather than being integral enough that it was more a necessity for the shoot than a challenge - and doing so is admirably ambitious; I’m not sure how many women would deliberately schedule the intense grind of making an independent film for their third trimester. As much as it likely, in some small way, freed Lowe up from having to think about the physical aspects of the performance as opposed to simply playing the Ruth’s personality, she’s a talented enough actress that this particular bit of authenticity likely wasn’t critical.

On the other hand, it does give her instant credibility with an audience often willing to simplify the idea of pregnancy when she goes to dark places. Ruth, see, hears her unborn child’s voice, and it often tells her to kill, because some person or other will eventually do her harm. It’s a brilliant twist on the usual plot of impending motherhood teaching a woman responsibility and self-sacrifice, as what Ruth is facing is not just the loss of independence and personal pleasure - for Ruth, impending motherhood is not just a fear of being unable to measure up to other people (or alternately repeating her own mother’s mistakes), but utter uncertainty that she’s doing the right thing at all. How can someone like her be a decent mother, even if her motives are good? Have all the changes to her body and the hormones affecting her mind made her someone else, who still has all the flaws she started with?

Full review on EFC.

”I am JUPITER I am the BIGGEST PLANET”

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

I’ve approached movies like “I Am Jupiter I Am the Biggest Planet” with some caution over the last few years, ever since Montreal’s Fantasia Festival concluded a FIlipino Cinema program with a hand-biting satire of the middle-class filmmakers there who make what folks call “poverty porn”, so it was good to see that this short film has much more than conspicuous commiseration to recommend it. It uses the slums of Manila and the wealthier people who scoop from there for their own gratification as a backdrop, but does so in the service of a tight story of people becoming dangerous when pushed to the brink.

Filmmaker Matthew Victor Pastor does a lot of clever things here - he introduces the characters at their own pace and lets the audience get to know them by their actions rather than talking themselves up, and he grounds the events in the location without making the film a polemic. There’s a bit of revenge fantasy to the film, and the contrast between realism and imagination is highlighted by the way he presents the film: It’s visually kind of flat and digital, consciously lacking a lot of fussy camerawork, but also very quiet, with what little speech there is presented as intertitles. It’s a fly-on-the-wall movie that is nonetheless very aware of its artifice, and generally uses both effectively.

Nong Hak (Dearest Sister)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

There’s no universal answer to how much attention should be paid to the living compared to the dead when crafting a ghost story, especially when you consider that a good one will do a great job in misdirecting the audience. Dearest Sister, for instance, puts the supernatural so near its center that it can easily look more important than it is, drawing conscious attention away from the more conventional material that it metaphorically extends. That’s kind of its job, and it does so successfully enough that it not making a lot of sense as a plot device can be quite forgivable.

Taking place in Laos, it inverts some of the traditional ways Westerners go about ghost stories. Nok (Amphiaiphun Phommapunya), for instance, heads into the city for her job working as a personal companion rather than to an isolated mansion. She’ll be helping her cousin Ana (Vilouna Phetmany) out where she can, as Ana is losing her sight and her Estonian husband Jakob (Tambet Tuisk) is frequently away on business. Nok is viewed with suspicion in both her new and old homes, with her immediate family thinking she’ll spend her time looking for a white fiance while Ana treats her country cousin as something between family and a servant, which makes the married couple who serve as maid (Manivanh Boulom) and gardener (Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy) even more hostile. It’s not exactly unwarranted, either; when Ana goes into trances and seems to see things from outside the normal world, Nok doesn’t shrink from exploiting those visions.

Nok arrives at Ana’s house quickly, too quickly to come across as a fish out of water, and that seems purposeful: The impression that forms with the audience is somebody between statuses; though she is actually in a pretty good position, she sees herself as potentially downgraded to a servant, and therefore needing to grab hold of the next level up to the extent that she can. Director Mattie Do and writer Christopher Larsen set the situation up in a way that seems so natural that it’s easy to sympathize with Nok even when she’s acting selfishly at first, with Amphaiphun Phommapunya always making sure that the audience sees how much of her can be explained as being young and in a new environment; her initial steps down a bad path come across as her being in over her head, keeping the audience with her enough to be invested in which way she’ll eventually lean.

Full review on EFC.

Mondo Yakuza

* * ¼ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

Mondo Yakuza isn’t quite an “amateurs making a movie for themselves and having fun” production with no commercial prospects, but it has that sort of energy, making it a fairly agreeable throwback to old-school grindhouse productions. I imagine that’s especially true if one’s old grindhouse played a lot of Seijun Suzuki, and in attempting to channel that particular Japanese auteur, these Aussie filmmakes have the room to push things pretty far and still not feel like parody, since what inspired them was so insane.

It starts rough, with a Japanese student telling her drug-dealer boyfriend that she doesn’t worry about danger too much, because her brother back home is yakuza and if anything happens to her, well, you know what would happen. The universe apparently sees that as too good a dare to ignore, so soon enough Ichiro Kataki (Kenji Shimada) is arriving in Australia, picking up a bunch of guns, and looking for the punk who killed his sister. That would be Ryan Beckett (Glenn Maynard), a raving thug who will inevitably wind up holed up in the home of his even more insane mother (Elizabeth O’Callaghan) with his at least comparatively sane brother Calvin (Rob Stanfield).

Though it’s got a vengeful yakuza injected into the middle of it, part of what makes this movie fun is that, while it doesn’t quite play as a spoof of contemporary Australian crime movies, it pretty clearly shares a lot of DNA with things like Chopper and Animal Kingdom (and likely dozens of others that didn’t make such a high-profile Pacific crossing), although it’s got the sort of over-the-top violence and characterization that more serious crime movies would pull back on. That’s actually a point in its favor at this budget level; fake blood is cheap to make and, let’s be honest, even if five not-great actors whose characters die gushing blood at regular intervals have the same amount of screen time as one guy with roughly the same talent in another movie, it’s more exciting and less wearing. The criminal day-to-day of the Beckett Boys isn’t particularly memorable, but it doesn’t completely feel like going through the motions, and the cast is at least given expansive personalities to play up rather than hanging blandly around until they can increase the body count. Rob Stanfield, in particular, brings out a lot of very entertaining frustration as the brother righteously angry that the family business, and likely his corpse, is going to get cut to pieces because his brother is a violent idiot.

Full review on EFC.

Free Fire

* * * ¾(out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas #1 (Monster Fest 2016, DCP)

Ben Wheatley has accumulated a cult fanbase by making films that strive to cut out the bits that aren’t in some way special, figuring that most people have seen enough movies to fill in the blanks or just go without if it means not seeing one more bloody scene of a local explaining his town’s weird history to the main character just because it’s going to play out later. At times, this gives his movies a thrill of discovery that they might not otherwise have; at its worst, this impulse can make movies like High-Rise seem perplexing and full of weirdos doing things at random. In Free Fire, it makes for a mainstream action movie that just doesn’t mess around, letting a crazy gunfight expand to fill almost the entire running time without making the audience wait around for the good parts.

The action takes place in 1978, where a number of lowlives have gathered in a Boston warehouse, looking to do an arms deal. Ord (Armie Hammer) is looking to buy, Vernon (Sharlto Copley) is looking to sell, and former Fed Justine (Brie Larson) is brokering the deal. Seems easy enough, but the guns Vernon brought aren’t the model Ord was looking for, and one of Vernon’s guys, Harry (Jack Reynor), has a serious beef with Stevo (Sam Riley), one of Ord’s. That would be enough to get people to start shooting, even if a double-cross wasn’t already inevitable.

So they start shooting at each other, and really don’t stop until the movie ends; moments of conversation generally involve the participants hiding behind whatever may provide them cover, speaking sotto voce to the person next to them or yelling across the open space. This doesn’t make it a dumb action movie at all, it turns out - the script by Wheatley and partner Amy Jump is full of tremendously funny bits, nd while they may have a character yell out in the middle that he’s forgotten which side he’s on, the plotting is certainly tighter than they could have gotten away with. As is their tendency, these filmmakers focus on what’s interesting and exciting, understanding that the audience really doesn’t care that much about the lives of these characters outside this room and thus not wasting any time with flashback and the bare minimum on set-up, dropping enough of what a viewer needs to not be jolted out of the film by wondering why that person is doing that thing which doesn’t make sense without killing the momentum.

Full review on EFC.

”Hell of a Day”

* * * (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas Rooftop (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

Though there are still a great many fans of post-apocalyptic scenarios, I’ve started to think that, unless the filmmaker has a genuinely creative way to use the situation as a metaphor for something else, I’d much rather see something like “Hell of a Day” than an extended slog through the end of the word: Give the audience a quick rush of gore and horror without giving it the time to get comfortable with what they’re seeing, and have them ready for the main feature within fifteen minutes. At this 15-minute scale, writer/director Evan Hughes can get the job done without the structure starting to feel hollow.

It’s a perfectly simple set-up - an injured girl played by Alexandra Octavia takes structure in an abandoned-looking inn, only to find that, no, she hasn’t left the living dead entirely behind, and trying to find a safe spot puts her in more danger. Hughes does a lot of things right here - the inn is a great setting whether he and the other filmmakers found it in a state of disrepair or dressed it up, dangerous-looking in its decay but also nightmarish for being a public gathering place so clearly bereft of people, for instance, and when things get bloody, he and make-up artist Liz Jenkins do not do things halfway; it’s genuinely gross. Octavia makes the audience believe that she might have the right attitude to react to the situation with the title, hardened and tough from getting through danger, but also weary and exhausted. And while the short doesn’t quite come full circle in the way that its makers seem to be aiming, it’s a nasty little puzzle box that clicks into place at the end.

The action and events of this movie could easily be the background for someone you see for ten minutes or less on The Walking Dead, and maybe that’s a part of what makes it fun - it reminds the viewer that the guys who wind up just being cannon fodder had their own horrific path to get there. It’s not deep, but it’s also not trying to stretch shallow until it looks deep, and that’s something for which a viewer can be grateful.

The Windmill Massacre (aka The Windmill)

* * ¾ (out of four)

Seen 26 November 2016 in Lido Cinemas Rooftop (Monster Fest 2016, digital)

There are plenty of horror movies out there that try to do what the guys making The Windmill Massacre do, but in some ways that makes its relatively modest target harder to hit: While so many are trying to stand out from the pack by being consciously aware of the genre’s structure or trying to elevate themselves to something greater, Nick Jongerius and his collaborators just build something that wouldn’t be out of place in a gruesome EC comic book, and while that may preclude it from later being remembered as one of the era’s great, influential horror movies, it works well enough in the present tense.

Meet Julie - no, scratch that, meet Jennifer Harris (Charlotte Beaumont), who fled her native Australia for Europe a few months ago, although the family that hired her as a nanny has just found out about her fake ID. She flees, hopping on the “Happy Holland Tours” bus when it feels like the police are closing in. It looks like a pretty fly-by-night outfit, with a motley crew also departing from Amsterdam to tour the windmills: Jackson (Ben Batt), a soldier with PTSD; Ruby Rousseau (Fiona Hampton), a former model trying to reinvent herself as a photographer; Curt West (Adam Thomas Wright), a kid just taken out of school by his father Douglas (Patrick Baladi) and strangely unable to get his mother on the phone; Nicholas Cooper (Noah Taylor), a former surgeon; Takashi Kido (Tanroh Ishida), a Japanese tourist whose grandmother wanted her ashes spread in the Netherlands; and Abe (Bart Klever), the tour guide. One windmill not on the tour, where a madman ground murder victims rather than grain, is said to just be a legend, although when the bus breaks down and they can’t find cellular service…

Jongerius and his co-writers (Chris W. Mitchell & Suzy Quid) don’t exactly create the next great slasher villain in Miller Hendrik (Kenan Raven); he doesn’t have a great visual hook to define him or the sort of personality that could carry him into a second movie, and while sequel-readiness isn’t necessary in general for horror movies or practical for this one - his murder weapon is not exactly what you’d call portable, so a follow-up would have to be almost a remake with new tourists - it’s often a good way to measure how enthusiastic one is about the villain in the present tense. There’s enough to Hendrik that I suspect the filmmakers could flesh him out a little given the opportunity, but in this movie, he never really seems to come out of the background, even when the Jongerius gets past the point of cutting away just before the thing following someone attacks.

Full review on EFC.

Sunday, August 02, 2015

The Fantasia Daily 2015.19 (1 August 2015): Battles Without Honor or Humanity, Sunrise, Poison Berry in My Brain, and Nina Forever

I'm generally a pretty good planner with this festival, so days like Saturday where I wind up seeing pretty much the opposite of what I laid out at the start are rare. But, last-minute-ish, I decided that 90+ minutes of "experimental" shorts was more than I can handle, and besides, one of the hosts entered a plea for more people to see Battles Without Honor or Humanity, so I did that even though I suspect it will play the Brattle sometime this fall. Sunrise got the nod over Manson Family Vacation, because even though I suspect it's got less Manson stuff than the name implies, I'm not big on "bonding over shared darkness", either. I actually stood between theaters hemming and hawing before choosing Poison Berry in My Brain over Orion, but a goofy Japanese romantic comedy sounded better than "post-apocalyptic but also its own kind of fantasy".

Nina Forever, at least, was going to be in the last slot of the night. Festival programmer Mitch Davis, who waxed extremely effusive, is on the left; co-writer/co-director Ben Blaine on the right. You know something is a small independent movie when the filmmakers are talking about how expensive it is to fly from the UK to Montreal, which is why only one of the team of brothers is there. Kind of a pity, because while it sounds like the original idea was Ben's, it also sounds like his brother Chris was the one to help him refine it into something that works as a movie, and it might have been really interesting to hear how that collaborative process worked from both participants.

Ben did talk about how the movie sprang more from one of the supporting characters' stories than the main thread, and wound up being revised into what it was as other ideas aggregated to it, including thoughts on female characters who exist mainly to help the main character deal with his issues. He also joked about how Cian Barry did an impressive job of making his character eventually boring, because that's how it kind of works - the "fixed" guy isn't quite the draw as the original version.

Today's plan: My whims could change, but I'm thinking Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet, The "Outer Limits of Animation" package, Experimenter, Ninja the Monster, and They Look Like People. Minuscule is fantastic, and folks I know from back home have their pretty good short "Postpartum" attached to the Lady Psycho Killer screening.

Jingi naki tatakai (Battles Without Honor or Humanity)

* * * * (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in the Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival: Retro & Restorations, DCP)

There's a pretty good mob movie in the middle of Battles Without Honor or Humanity, but it is with the ends that make it brilliant: It starts with images of the mushroom cloud and Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the war, but then jumps into images so frantic that it's almost impossible to absorb them fully - even when they're freeze-framed, it's on a blur. Director Kinji Fukasaku is making introductions, but most characters will need a second appearance to be recognized.

It finishes with a funeral, as it must with all the violence being handed out, but one where the disgust at all the violence can't overcome how it is the only thing some of these guys, including the one making the statement, know.

In between, Fukasaku and the writers tell a story that plays like a rapid fire recitation of events - dates appear on-screen, narration fills in gaps, and the main character is sidelined as the film follows the events of the yakuza wars in Kure City, Hiroshima, and only the highlights. As that does on, though, the film starts making that a statement about how, despite whatever romantic notions Shozo Hirono (Bunta Sugawara) may have had about the yakuza before, the modern version is about little more than self-perpetuation and protection. Any of the historical tendencies of the yakuza to be part of the community, and any forays into legitimate business, are in the background. Fukasaku keeps things exciting, sure, but also makes sure that the hollowness of the action is never far behind.

It's almost having your cake and eating it too, and the ability to pull that off makes Battles perhaps one of the greatest crime films ever made.

Full review on EFC.

Sunrise

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in the J.A. de Seve Cinema (Fantasia International Film Festival, DCP)

Writer/director Partho Sen-Gupta takes certain things very literally in Sunrise, but it's kind of a delight when he does, because the effect is nifty and exhilarating in the midst of a film that can use a bit of that as it tries to sap the audience's hope. Even with the obvious flourishes, he's still made a tight film that may obviously trumpet its cause but is engrossing nevertheless.

Child abductions are frighteningly common in India; Inspector Lakshum Joshi (Adil Hussain) of the Mumbai Police Social Services Division foils one on his way home from work one night, although he is unable to catch the perpetrator, seemingly losing his trail at Paradise, a fancy-looking nightclub out of place in this run-down neighborhood. the next day at work, another missing girl is reported, and we soon see Naina (Esha Amlani), about seven, brought into a "dorm" with mostly teenage girls with one, Komal (Gulnaaz Ansari), told to look after her. It's one of many such cases the under-staffed, under-funded department has to investigate, and Joshi is still reeling from his own daughter Aruna (Komal Gupta) being taken from in front of her school - made worse by coming home to his wife Leela (Tannishta Chatterjee), whose mind seems to have completely rejected that Aruna is gone.

I suspect that most filmmakers in India do everything they can to avoid monsoon season, but Sen-Gupta embraces it here, shooting nearly every exterior scene in a torrential downpour and having it audible on the soundtrack when inside. It's a numbing sound that sometimes seems to keep the squad inside and at their desks, sending out alerts to other departments but often seeming inactive and ineffective. It's reinforced when Joshi will spot something and run after it, getting drenched or running through streets where the water is above his ankles. Attacking the problem seems to get them nowhere and coming out when things have run their course and there's a body to deal with becomes a pain.

Full review on EFC.

Nounai Poison Berry (Poison Berry in My Brain)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival, DCP)

I'm not sure when Inside Out opened in Japan, but I do wonder how many folks there saw it as less incredibly creative and insightful compared to their American counterparts, considering that the Poison Berry in My Brain manga has been running since 2009 and this live-action adaptation came out in May. The similarities are obvious - a female protagonist with a committee of five personality fragments debating over her next actions in her head, and some similar imagery - although I suspect that the romantic comedy plot gives it much less heft than Pixar's movie made for a younger audience.

There are times when being a romantic comedy makes Poison Berry rather frustrating - it keeps what is going on in the head of Ichiko Sakurai (Yoko Maki) too focused on one aspect of her life when there is clearly more going on; for example, that she's writing a novel sometimes seems more like a way to bring an alternate suitor into her life than a major deal on its own. It also obscures that her near-paralysis when it comes time to make decisions is perhaps the root of her problems, which should make the "internal" story focus more on how her various personality traits can work together, and the screenplay by Tomoko Aizawa doesn't have a great grasp on that. It seems even more unhealthy in terms of how it deals with Ichiko's sexuality, although that may come from Setona Mizushiro's source material.

For all its stumbles, though, it's frequently very funny, especially with the rapid-fire debates going on inside her head. Ryunosuke Kamiki and Yo Yoshida are an opposites-attract pair themselves as her optimism and neurosis, and young Hiyori Sakurada is almost always hilarious as her impulsive side, especially when those impulses sound a week bit more adult than the child used to represent them. Yoko Maki may wind up having to play indecision or blurt out things that don't make real-world sense as a result of what's going on with Ichiko's committee, but she's also tremendously charming on her own, though neither Yuki Furukawa as her younger boyfriend or Songha as her smitten editor ever seems like a great pairing.

Indeed, there are a few times I wished Poison Berry in My Brain could have been about everything in Ichiko's life besides dating; it's where Maki is the most magnetic and the film's tendency to avoid sexuality as part of her personality rather than something which occcasionally overwhelms it would be the least troublesome. It's still very entertaining despite that, and maybe there would be room for that in a sequel.

Full review on EFC.

"Teeth" (2015)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival, HD)

Well, that's a weird one.

It's impressive what filmmakers Tom Brown & Daniel Gray do in this animated production, making something simple like gaining and losing teeth seem really disturbing thanks to their not-quite-grotesque but certainly unpretty art style, sinister narration by Richard E. Grant, and the peculiar words put in his mouth about seeing ones own teeth as abominations until realizing how that attitude is affecting how one enjoys food. The laughter during that part of the film was about fifty-fifty between sincere and nervous, and I kind of like that; you don't see that reaction too often.

After that, though, it gets downright weird, although a seven-minute short is a good use for that sort of weird; it's the sort of thing that would probably be background creepiness in a typical horror movie given a couple minutes to play out in the foreground here. Then, just as it starts to strain credulity, they end it with a gross but entertainingly absurd gag.

Not for everyone, but I think these guys hit their target, and folks who have the same sort of sense of humor should really like it.

Nina Forever

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival, DCP)

Ben & Chris Blaine have a heck of a great idea for a movie here - when a Rob (Cian Barry), who tried to commit suicide after the death of his girlfriend but failed, starts seeing Holly (Abigail Hardingham), there are certain weird things about the relationship, but none more than how the bloody, back-broken, naked Nina (Fiona O'Shaughnessy) starts appearing when they have sex. That is something to get past.

It's a really neat trick, actually - as much as hauntings and sex are often connected in horror movies, it's usually immediately violent either in terms of murder or rape (because she doesn't realize who/what she's actually sleeping with at that moment), while Nina mostly brings hurtful words and major cleaning issues. I've mentioned before that ghosts are best used as the past given form, and Nina fits that description perfectly. O'Shaughnessey's dialogue can sometimes be a little hard to make out, but the words that the Blaines give her really nail how the past can be both tremendously cruel and utterly uncaring at the same time, and the film eventually goes into interesting places with where her presence comes from.

And while I stumbled a bit on O'Shaughnessey's accent, her physicality in the role is kind of incredible - she moves a bit, but it's mostly flopping around, feeling like a dead thing without lurches that seem rather ridiculous after seeing this. Barry handles Rob's self-pity well, never making it obviously overwhelming enough for him to not be appealing, and Abigail Hardingham is terrific as Holly. She does a great job of handling how, despite her obvious sex appeal and heart-covered sweaters, she's pretty dark inside despite also having a core that, in most things, really wants to be helpful.

Full review on EFC.

Nina Forever, at least, was going to be in the last slot of the night. Festival programmer Mitch Davis, who waxed extremely effusive, is on the left; co-writer/co-director Ben Blaine on the right. You know something is a small independent movie when the filmmakers are talking about how expensive it is to fly from the UK to Montreal, which is why only one of the team of brothers is there. Kind of a pity, because while it sounds like the original idea was Ben's, it also sounds like his brother Chris was the one to help him refine it into something that works as a movie, and it might have been really interesting to hear how that collaborative process worked from both participants.

Ben did talk about how the movie sprang more from one of the supporting characters' stories than the main thread, and wound up being revised into what it was as other ideas aggregated to it, including thoughts on female characters who exist mainly to help the main character deal with his issues. He also joked about how Cian Barry did an impressive job of making his character eventually boring, because that's how it kind of works - the "fixed" guy isn't quite the draw as the original version.

Today's plan: My whims could change, but I'm thinking Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet, The "Outer Limits of Animation" package, Experimenter, Ninja the Monster, and They Look Like People. Minuscule is fantastic, and folks I know from back home have their pretty good short "Postpartum" attached to the Lady Psycho Killer screening.

Jingi naki tatakai (Battles Without Honor or Humanity)

* * * * (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in the Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival: Retro & Restorations, DCP)

There's a pretty good mob movie in the middle of Battles Without Honor or Humanity, but it is with the ends that make it brilliant: It starts with images of the mushroom cloud and Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the war, but then jumps into images so frantic that it's almost impossible to absorb them fully - even when they're freeze-framed, it's on a blur. Director Kinji Fukasaku is making introductions, but most characters will need a second appearance to be recognized.

It finishes with a funeral, as it must with all the violence being handed out, but one where the disgust at all the violence can't overcome how it is the only thing some of these guys, including the one making the statement, know.

In between, Fukasaku and the writers tell a story that plays like a rapid fire recitation of events - dates appear on-screen, narration fills in gaps, and the main character is sidelined as the film follows the events of the yakuza wars in Kure City, Hiroshima, and only the highlights. As that does on, though, the film starts making that a statement about how, despite whatever romantic notions Shozo Hirono (Bunta Sugawara) may have had about the yakuza before, the modern version is about little more than self-perpetuation and protection. Any of the historical tendencies of the yakuza to be part of the community, and any forays into legitimate business, are in the background. Fukasaku keeps things exciting, sure, but also makes sure that the hollowness of the action is never far behind.

It's almost having your cake and eating it too, and the ability to pull that off makes Battles perhaps one of the greatest crime films ever made.

Full review on EFC.

Sunrise

* * * ½ (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in the J.A. de Seve Cinema (Fantasia International Film Festival, DCP)

Writer/director Partho Sen-Gupta takes certain things very literally in Sunrise, but it's kind of a delight when he does, because the effect is nifty and exhilarating in the midst of a film that can use a bit of that as it tries to sap the audience's hope. Even with the obvious flourishes, he's still made a tight film that may obviously trumpet its cause but is engrossing nevertheless.

Child abductions are frighteningly common in India; Inspector Lakshum Joshi (Adil Hussain) of the Mumbai Police Social Services Division foils one on his way home from work one night, although he is unable to catch the perpetrator, seemingly losing his trail at Paradise, a fancy-looking nightclub out of place in this run-down neighborhood. the next day at work, another missing girl is reported, and we soon see Naina (Esha Amlani), about seven, brought into a "dorm" with mostly teenage girls with one, Komal (Gulnaaz Ansari), told to look after her. It's one of many such cases the under-staffed, under-funded department has to investigate, and Joshi is still reeling from his own daughter Aruna (Komal Gupta) being taken from in front of her school - made worse by coming home to his wife Leela (Tannishta Chatterjee), whose mind seems to have completely rejected that Aruna is gone.

I suspect that most filmmakers in India do everything they can to avoid monsoon season, but Sen-Gupta embraces it here, shooting nearly every exterior scene in a torrential downpour and having it audible on the soundtrack when inside. It's a numbing sound that sometimes seems to keep the squad inside and at their desks, sending out alerts to other departments but often seeming inactive and ineffective. It's reinforced when Joshi will spot something and run after it, getting drenched or running through streets where the water is above his ankles. Attacking the problem seems to get them nowhere and coming out when things have run their course and there's a body to deal with becomes a pain.

Full review on EFC.

Nounai Poison Berry (Poison Berry in My Brain)

* * * (out of four)

Seen 1 August 2015 in Theatre Hall Concordia (Fantasia International Film Festival, DCP)

I'm not sure when Inside Out opened in Japan, but I do wonder how many folks there saw it as less incredibly creative and insightful compared to their American counterparts, considering that the Poison Berry in My Brain manga has been running since 2009 and this live-action adaptation came out in May. The similarities are obvious - a female protagonist with a committee of five personality fragments debating over her next actions in her head, and some similar imagery - although I suspect that the romantic comedy plot gives it much less heft than Pixar's movie made for a younger audience.

There are times when being a romantic comedy makes Poison Berry rather frustrating - it keeps what is going on in the head of Ichiko Sakurai (Yoko Maki) too focused on one aspect of her life when there is clearly more going on; for example, that she's writing a novel sometimes seems more like a way to bring an alternate suitor into her life than a major deal on its own. It also obscures that her near-paralysis when it comes time to make decisions is perhaps the root of her problems, which should make the "internal" story focus more on how her various personality traits can work together, and the screenplay by Tomoko Aizawa doesn't have a great grasp on that. It seems even more unhealthy in terms of how it deals with Ichiko's sexuality, although that may come from Setona Mizushiro's source material.